TMEP / Substantive Examination of Applications

Substantive Examination of Applications

1201 Ownership of Mark

Under §1(a)(1) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1051(a)(1) , a trademark or service mark application based on use in commerce must be filed by the owner of the mark. A §1(a) application must include a verified statement that the applicant believes the applicant is the owner of the mark sought to be registered. 15 U.S.C. §1051(a)(3)(A) ; 37 C.F.R. §2.33(b)(1) . An application that is not filed by the owner is void. See TMEP §1201.02(b) .

A trademark or service mark application under §1(b) or §44 of the Act, 15 U.S.C. §§1051(b) , 1126 , must be filed by a party who is entitled to use the mark in commerce, and must include a verified statement that the applicant is entitled to use the mark in commerce and that the applicant has a bona fide intention to use the mark in commerce as of the application filing date. 15 U.S.C. §§1051(b)(3)(A)-(B) , 1126(d)(2) , 1126(e) ; 37 C.F.R. §2.33(b)(2) . When the person designated as the applicant is not the person with a bona fide intention to use the mark in commerce, the application is void. See TMEP §1201.02(b) .

In a §1(b) application, before the mark can be registered, the applicant must file an amendment to allege use under 15 U.S.C. §1051(c) ( see TMEP §§1104-1104.11 ) or a statement of use under 15 U.S.C. §1051(d) ( see TMEP §§1109-1109.18 ) which states that the applicant is the owner of the mark. 15 U.S.C. §1051(b) ; 37 C.F.R. §§2.76(b)(1)(i) , 2.88(b)(1)(i) .

In a §44 application, the applicant must be the owner of the foreign application or registration on which the U.S. application is based as of the filing date of the U.S. application. See TMEP §1005 .

An application under §66(a) of the Trademark Act (i.e. ,a request for extension of protection of an international registration to the United States under the Madrid Protocol), must be filed by the holder of the international registration. 15 U.S.C. §1141e(a) ; 37 C.F.R. §7.25 . The application must include a verified statement that the applicant has a bona fide intention to use the mark in commerce. 15 U.S.C. §1141(f)(a) ; 37 C.F.R. §2.33(e)(1) . The verified statement in a §66(a) application for a trademark or service mark is part of the international registration on file at the International Bureau of the World Intellectual Property Organization (“IB”). The IB will have established that the international registration includes this verified statement before it sends the request for extension of protection to the United States Patent and Trademark Office (“USPTO”). See TMEP §804.05 . The request for extension of protection remains part of the international registration, and ownership is determined by the IB. See TMEP §501.07 regarding assignment of §66(a) applications.

The provisions discussed above also apply to collective and certification marks with the caveat that the owner of such marks does not use the mark or have a bona fide intention to do so, but rather exercises control over its use by members/authorized users or has a bona fide intention, and is entitled, to exercise such control over the use by members/authorized users. See 15 U.S.C. §§1053 , 1054 ; TMEP §§1303.02(a) , 1304.03(a) , 1306.01(a) .

1201.01 Claim of Ownership May Be Based on Use By Related Companies

In an application under §1 of the Trademark Act, an applicant may base its claim of ownership of a trademark or a service mark on:

- (1) its own exclusive use of the mark;

- (2) use of the mark solely by a related company whose use inures to the applicant’s benefit ( see TMEP §§1201.03–1201.03(e) ); or

- (3) use of the mark both by the applicant and by a related company whose use inures to the applicant’s benefit ( see TMEP §1201.05 ).

Where the mark is used by a related company, the owner is the party who controls the nature and quality of the goods sold or services rendered under the mark. The owner is the only proper party to apply for registration. 15 U.S.C. §1051 . See Moreno v. Pro Boxing Supplies, Inc., 124 USPQ2d 1028, 1036 (TTAB 2017) (finding that a mere licensee cannot rely on licensor’s use to prove priority). See TMEP §§1201.03–1201.03(e) for additional information about use by related companies.

The examining attorney should accept the applicant’s statement regarding ownership of the mark unless it is clearly contradicted by information in the record. In re L. A. Police Revolver & Athletic Club, Inc. , 69 USPQ2d 1630 (TTAB 2003).

The USPTO does not inquire about the relationship between the applicant and other parties named on the specimen or elsewhere in the record, except when the reference to another party clearly contradicts the applicant’s verified statement that it is the owner of the mark or entitled to use the mark. Moreover, where the application states that use of the mark is by a related company or companies, the examining attorney should not require any explanation of how the applicant controls such use.

The provisions discussed above also apply to service marks, collective marks, and certification marks, except that, by definition, collective and certification marks are not used by the owner of the mark, but are used by others under the control of the owner. See 15 U.S.C. §§1053 , 1054 ; TMEP §§1303.02(a) , 1304.03(a) , 1306.01(a) . In addition, an application for registration of a collective mark must specify the nature of the applicant’s control over use of the mark. 37 C.F.R. §2.44(a)(4)(i)(A) ; TMEP §1303.01(a)(i)(A) .

See TMEP §1201.04 for information about when an examining attorney should issue an inquiry or refusal with respect to ownership.

1201.02 Identifying the Applicant in the Application

1201.02(a) Identifying the Applicant Properly

The applicant may be any person or entity capable of suing and being sued in a court of law. See TMEP §§803-803.03(k) for the appropriate format for identifying the applicant and setting forth the relevant legal entity.

1201.02(b) Application Void if Wrong Party Identified as the Applicant

An application must be filed by the party who is the owner of (or is entitled to use) the mark as of the application filing date. See TMEP §1201 .

An application based on use in commerce under 15 U.S.C. §1051(a) must be filed by the party who owns the mark on the application filing date. If the applicant does not own the mark on the application filing date, the application is void. 37 C.F.R. §2.71(d) ; ); Lyons v. Am. Coll. of Veterinary Sports Med. & Rehab. , 859 F.3d 1023, 1027, 123 USPQ2d 1024, 1027 (Fed. Cir. 2017); Conolty v. Conolty O’Connor NYC LLC, 111 USPQ2d 1302, 1309 (TTAB 2014); see Huang v. Tzu Wei Chen Food Co., 849 F.2d 1458, 7 USPQ2d 1335 (Fed. Cir. 1988); Great Seats, Ltd. v. Great Seats, Inc. , 84 USPQ2d 1235, 1239 (TTAB 2007).

If the record indicates that the applicant is not the owner of the mark, the examining attorney should refuse registration on that ground. The statutory basis for this refusal is §1 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1051 , and, where related company issues are relevant, §§5 and 45 of the Act, 15 U.S.C. §§1055 , 1127 . The examining attorney should not have the filing date cancelled or refund the application filing fee.

In an application under §1(b) or §44 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1051(b) , §1126 , the applicant must be entitled to use the mark in commerce on the application filing date, and the application must include a verified statement that the applicant has a bona fide intention to use the mark in commerce. 15 U.S.C. §§1051(b)(3)(A) , 1051(b)(3)(B) , 1126(d)(2) , 1126(e) . When the person designated as the applicant was not the person with a bona fide intention to use the mark in commerce at the time the application was filed, the application is void. Am. Forests v. Sanders, 54 USPQ2d 1860, 1864 (TTAB 1999), (holding an intent-to-use application filed by an individual void, where the entity that had a bona fide intention to use the mark in commerce on the application filing date was a partnership composed of the individual applicant and her husband), aff’d, 232 F.3d 907 (Fed. Cir. 2000) . However, the examining attorney will not inquire into the bona fides, or good faith, of an applicant’s asserted intention to use a mark in commerce during ex parte examination, unless there is evidence in the record clearly indicating that the applicant does not have a bona fide intention to use the mark in commerce. See TMEP §1101.

When an application is filed in the name of the wrong party, this defect cannot be cured by amendment or assignment. 37 C.F.R. §2.71(d) ; TMEP §803.06 . However, if the application was filed by the owner, but there was a mistake in the manner in which the applicant’s name was set forth in the application, this may be corrected. See TMEP §1201.02(c) for examples of correctable and non-correctable errors.

See TMEP §1201 regarding ownership of a §66(a) application.

1201.02(c) Correcting Errors in How the Applicant Is Identified

If the party applying to register the mark is, in fact, the owner of the mark, but there is a mistake in the manner in which the name of the applicant is set out in the application, the mistake may be corrected by amendment. U.S. Pioneer Elec. Corp. v. Evans Mktg., Inc. , 183 USPQ 613 (Comm’r Pats. 1974). However, the application may not be amended to designate another entity as the applicant. 37 C.F.R. §2.71(d) ; TMEP §803.06 . An application filed in the name of the wrong party is void and cannot be corrected by amendment. 37 C.F.R. §2.71(d) ; see Huang v. Tzu Wei Chen Food Co., 849 F.2d 1458, 7 USPQ2d 1335 (Fed. Cir. 1988); Great Seats, Ltd. v. Great Seats, Inc. , 84 USPQ2d 1235, 1244 (TTAB 2007); In re Tong Yang Cement Corp., 19 USPQ2d 1689 (TTAB 1991).

Correctable Errors. The following are examples of correctable errors in identifying the applicant:

- (1) Trade Name Set Forth as Applicant. If the applicant identifies itself by a name under which it does business, which is not a legal entity, then amendment to state the applicant’s correct legal name is permitted. Cf. In re Atl. Blue Print Co. , 19 USPQ2d 1078 (Comm’r Pats 1990) (finding that Post Registration staff erred in refusing to allow amendment of affidavit under 15 U.S.C. §1058 to show registrant’s corporate name rather than registrant’s trade name).

- (2) Operating Division Identified as Applicant. If the applicant mistakenly names an operating division, which by definition is not a legal entity, as the owner, then the applicant’s name may be amended. See TMEP §1201.02(d) .

- (3) Minor Clerical Error. Minor clerical errors such as the mistaken addition or omission of “The” or “Inc.” in the applicant’s name may be corrected by amendment, as long as this does not result in a change of entity. However, change of a significant portion of the applicant’s name is not considered a minor clerical error.

- (4) Inconsistency in Original Application as to Owner Name or Entity . If the original application reflects an inconsistency between the owner name and the entity type, for example, an individual and a corporation are each identified as the owner in different places in the application, the application may be amended to clarify the inconsistency.

Example: Inconsistency Between Owner Section and Entity Section of TEAS Form: If the information in the “owner section” of a TEAS application form is inconsistent with the information in the “entity section” of the form, the inconsistency can be corrected, for example, if an individual is identified as the owner and a corporation is listed as the entity, the application may be amended to indicate the proper applicant name/entity.

Signature of Verification by Different Entity Does Not Create Inconsistency . In view of the broad definition of a “person properly authorized to sign on behalf of the [applicant]” in 37 C.F.R. §2.193(e)(1) ( see TMEP §611.03(a) ), if the person signing an application refers to a different entity, the USPTO will presume that the person signing is an authorized signatory who meets the requirements of 37 C.F.R. §2.193(e)(1) , and will not issue an inquiry regarding the inconsistency or question the signatory’s authority to sign. If the applicant later requests correction to identify the party who signed the verification as the owner, the USPTO will not allow the amendment. For example, if the application is filed in the name of “John Jones, individual U.S. citizen,” the verification is signed by “John Jones, President of ABC Corporation,” and the applicant later proposes to amend the application to show ABC Corporation as the owner, the USPTO will not allow the amendment, because there was no inconsistency in the original application as to the owner name/entity.

- (5) Change of Name. If the owner of a mark legally changed its name before filing an application, but mistakenly lists its former name on the application, the error may be corrected, because the correct party filed, but merely identified itself incorrectly. In re Techsonic Indus., Inc., 216 USPQ 619 (TTAB 1982).

- (6) Partners Doing Business as Partnership. If an applicant has been identified as “A and B, doing business as The AB Company, a partnership,” and the true owner is a partnership organized under the name The AB Company and composed of A and B, the applicant’s name should be amended to “The AB Company, a partnership composed of A and B.”

- (7) Non-Existent Entity. If the party listed as the applicant did not exist on the application filing date, the application may be amended to correct the applicant’s name. See Accu Pers. Inc. v. Accustaff Inc., 38 USPQ2d 1443 (TTAB 1996) (holding application not void ab initio where corporation named as applicant technically did not exist on filing date, since four companies who later merged acted as a single commercial enterprise when filing the application); Argo & Co. v. Springer, 198 USPQ 626, 635 (TTAB 1978) (holding that application may be amended to name three individuals as joint applicants in place of an originally named corporate applicant which was never legally incorporated, because the individuals and non-existent corporation were found to be the same, single commercial enterprise); Pioneer Elec., 183 USPQ 613 (holding that applicant’s name may be corrected where the application was mistakenly filed in the name of a fictitious and non-existent party).

Example 1: If the applicant is identified as ABC Company, a Delaware partnership, and the true owner is ABC LLC, a Delaware limited liability company, the application may be amended to correct the applicant’s name and entity if the applicant states on the record that “ABC Company, a Delaware partnership, did not exist as a legal entity on the application filing date.”

Example 2: If an applicant is identified as “ABC Corporation, formerly known as XYZ, Inc.,” and the correct entity is “XYZ, Inc.,” the applicant’s name may be amended to “XYZ, Inc.” as long as “ABC Corporation, formerly known as XYZ, Inc.” was not a different existing legal entity. Cf. Custom Computer Serv. Inc. v. Paychex Prop. Inc. , 337 F.3d 1334, 1337, 67 USPQ2d 1638, 1640 (Fed. Cir. 2003) (holding that the term “mistake,” within the context of the rule regarding the misidentification of the person in whose name an extension of time to file an opposition was requested, means a mistake in the form of the potential opposer’s name or its entity type and does not encompass the recitation of a different existing legal entity that is not in privity with the party that should have been named).

To correct an obvious mistake of this nature, a verification or declaration is not normally necessary.

Non-Correctable Errors. The following are examples of non-correctable errors in identifying the applicant:

- (1) President of Corporation Files as Individual. If the president of a corporation is identified as the owner of the mark when in fact the corporation owns the mark, and there is no inconsistency in the original application between the owner name and the entity type (such as a reference to a corporation in the entity section of the application), the application is void as filed because the applicant is not the owner of the mark.

- (2) Predecessor in Interest. If an application is filed in the name of entity A, when the mark was assigned to entity B before the application filing date, the application is void as filed because the applicant was not the owner of the mark at the time of filing. Cf. Huang, 849 F.2d at 1458, 7 USPQ2d at 1335 (holding as void an application filed by an individual two days after ownership of the mark was transferred to a newly formed corporation).

- (3) Joint Venturer Files. If the application is filed in the name of a joint venturer when the mark is owned by the joint venture, and there is no inconsistency in the original application between the owner name and the entity type (such as a reference to a joint venture in the entity section of the application), the applicant’s name cannot be amended. Tong Yang Cement, 19 USPQ2d at 1689.

- (4) Sister Corporation. If an application is filed in the name of corporation A and a sister corporation (corporation B) owns the mark, the application is void as filed, because the applicant is not the owner of the mark. Great Seats, 84 USPQ2d at 1244 (holding §1(a) application void where the sole use and advertising of the mark was made by a sister corporation who shared the same president, controlling shareholder, and premises as the applicant).

- (5) Parent/Subsidiary. If an application is filed in the name of corporation A, a wholly owned subsidiary, and the parent corporation (corporation B) owns the mark, the application is void as filed because the applicant is not the owner of the mark. See TMEP §1201.03(b) regarding wholly owned related companies.

- (6) Joint Applicants. If an application owned by joint applicants is filed in the name of one of the owners and another party who is not the joint owner, the application is void as filed because the listed parties did not own the mark as joint applicants. Cf. Am. Forests v. Sanders, 54 USPQ2d 1860 (TTAB 1999) (application filed in the name of an individual, when it was actually owned by a partnership composed of the individual and her husband, was void ab initio).

1201.02(d) Operating Divisions

An operating division that is not a legal entity that can sue and be sued does not have standing to own a mark or to file an application to register a mark. The application must be filed in the name of the company of which the division is a part. In re Cambridge Digital Sys., 1 USPQ2d 1659, 1660 n.1 (TTAB 1986) . An operating division’s use is considered to be use by the applicant and not use by a related company; therefore, reference to related-company use is permissible but not necessary.

1201.02(e) Changes in Ownership After Application Is Filed

See TMEP Chapter 500 regarding changes of ownership and changes of name subsequent to filing an application for registration, and TMEP §§502.02–502.02(b) regarding the procedure for requesting that a certificate of registration be issued in the name of an assignee or in an applicant’s new name.

1201.03 Use by Related Companies

Section 5 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1055 , states, in part, as follows:

Where a registered mark or a mark sought to be registered is or may be used legitimately by related companies, such use shall inure to the benefit of the registrant or applicant for registration, and such use shall not affect the validity of such mark or of its registration, provided such mark is not used in such manner as to deceive the public.

Section 45 of the Act, 15 U.S.C. §1127 , defines “related company” as follows:

The term “related company” means any person whose use of a mark is controlled by the owner of the mark with respect to the nature and quality of the goods or services on or in connection with which the mark is used.

Thus, §5 of the Act permits applicants to rely on use of the mark by related companies. Either a natural person or a juristic person may be a related company. 15 U.S.C. §1127 .

The essence of related-company use is the control exercised over the nature and quality of the goods or services on or in connection with which the mark is used. Noble House Home Furnishings, LLC v. Floorco Enters., LLC, 118 USPQ2d 1413, 1421 (TTAB 2016). When a mark is used by a related company, use of the mark inures to the benefit of the party who controls the nature and quality of the goods or services. Id. This party is the owner of the mark and, therefore, the only party who may apply to register the mark. Smith Int’l. Inc. v. Olin Corp., 209 USPQ 1033, 1044 (TTAB 1981).

Reliance on related-company use requires, inter alia , that the related company use the mark in connection with the same goods or services recited in the application. In re Admark, Inc., 214 USPQ 302, 303 (TTAB 1982) (finding that related-company use was not at issue where the applicant sought registration of a mark for advertising-agency services and the purported related company used the mark for retail-store services).

A related company is different from a successor in interest who is in privity with the predecessor in interest for purposes of determining the right to register. Wells Cargo, Inc. v. Wells Cargo, Inc. , 197 USPQ 569, 570 (TTAB 1977), aff’d,606 F.2d 961, 203 USPQ 564 (C.C.P.A. 1979).

See TMEP §1201.03(b) regarding wholly owned related companies, §1201.03(c) regarding corporations with common stockholders, directors, or officers, §1201.03(d) regarding sister corporations, and §1201.03(e) regarding license and franchise situations.

1201.03(a) No Explanation of Use of Mark by Related Companies or Applicant’s Control Over Use of Mark by Related Companies Required

The USPTO does not require an application to specify if the applied-for mark is not being used by the applicant but is being used by one or more related companies whose use inures to the benefit of the applicant under §5 of the Act. Moreover, where the application states that use of the mark is by a related company or companies, the USPTO does not require an explanation of how the applicant controls the use of the mark.

Additionally, the USPTO does not inquire about the relationship between the applicant and other parties named on the specimen or elsewhere in the record, except when the reference to another party clearly contradicts the applicant’s verified statement that it is the owner of the mark or entitled to use the mark. See TMEP §1201.04 . In such cases, the USPTO may require such details concerning the nature of the relationship and such proofs as may be necessary and appropriate for the purpose of showing that the use by related companies inures to the benefit of the applicant and does not affect the validity of the mark. 37 C.F.R. §2.38(b) .

1201.03(b) Wholly Owned Related Companies

Frequently, related companies comprise parent and wholly owned subsidiary corporations. Either a parent corporation or a subsidiary corporation may be the proper applicant, depending on the facts concerning ownership of the mark. The USPTO will consider the filing of the application in the name of either the parent or the subsidiary to be the expression of the intention of the parties as to ownership in accord with the arrangements between them. However, once the application has been filed in the name of either the parent or the wholly owned subsidiary, the USPTO will not permit an amendment of the applicant’s name to specify the other party as the owner. The applicant’s name can be changed only by assignment.

Furthermore, once an application has been filed in the name of either the parent or the wholly owned subsidiary, the USPTO will not consider documents (e.g., statements of use under 15 U.S.C. §1051(d) or affidavits of continued use or excusable nonuse under 15 U.S.C. §1058 ) filed in the name of the other party to have been filed by the owner. See In re Media Cent. IP Corp., 65 USPQ2d 1637 (Dir USPTO 2002) (holding §8 affidavit filed in the name of a subsidiary and predecessor in interest of the current owner unacceptable); In re ACE III Commc’ns, Inc. , 62 USPQ2d 1049 (Dir USPTO 2001) (holding §8 affidavit unacceptable where the owner of the registration was a corporation, and the affidavit was filed in the name of an individual who asserted that she was the owner of the corporation).

Either an individual or a juristic entity may own a mark that is used by a wholly owned related company. In re Hand , 231 USPQ 487 (TTAB 1986).

1201.03(c) Common Stockholders, Directors, or Officers

Corporations are not “related companies” within the meaning of §5 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1055 , merely because they have the same stockholders, directors, or officers, or because they occupy the same premises. Great Seats, Ltd. v. Great Seats, Inc. , 84 USPQ2d 1235, 1243 (TTAB 2007) (holding that the fact that both the applicant corporation and the corporate user of the mark have the same president and controlling stockholder, and share the same premises, does not make them related companies); In re Raven Marine, Inc. , 217 USPQ 68, 69 (TTAB 1983) ( holding statement that both the applicant corporation and the corporate user of the mark have the same principal stockholder and officer insufficient to show that the user is a related company).

If an individual applicant is not the sole owner of the corporation that is using the mark, the question of whether the corporation is a “related company” depends on whether the applicant maintains control over the nature and quality of the goods or services such that use of the mark inures to the applicant’s benefit. A formal written licensing agreement between the parties is not necessary, nor is its existence sufficient to establish ownership rights. The critical question is whether the applicant sufficiently controls the nature and quality of the goods or services with which the mark is used. See Pneutek, Inc. v. Scherr, 211 USPQ 824, 833 (TTAB 1981) (holding that the applicant, an individual, exercised sufficient control over the nature and quality of the goods sold under the mark by the licensee that the license agreement vested ownership of the mark in the applicant).

Similarly, where an individual applicant is not the sole owner of the corporation that is using the mark, the fact that the individual applicant is a stockholder, director, or officer in the corporation is insufficient in itself to establish that the corporation is a related company. The question depends on whether the applicant maintains control over the nature and quality of the goods or services.

See TMEP §1201.03(b) regarding use by wholly owned related companies.

1201.03(d) Sister Corporations

The fact that two sister corporations are controlled by a single parent corporation does not mean that they are related companies. Where two corporations are wholly owned subsidiaries of a common parent, use by one sister corporation is not considered to inure to the benefit of the other, unless the applicant sister corporation exercises appropriate control over the nature and quality of the goods or services on or in connection with which the mark is used. Great Seats, Ltd. v. Great Seats, Inc. , 84 USPQ2d 1235, 1242 (TTAB 2007); In re Pharmacia Inc. , 2 USPQ2d 1883, 1884 (TTAB 1987); Greyhound Corp. v. Armour Life Ins. Co. , 214 USPQ 473, 475 (TTAB 1982).

See TMEP §1201.03(b) regarding use by wholly owned related companies.

1201.03(e) License and Franchise Situations

The USPTO accepts applications by parties who claim to be owners of marks through use by controlled licensees, pursuant to a contract or agreement. Pneutek, Inc. v. Scherr, 211 USPQ 824, 833 (TTAB 1981).

A controlled licensing agreement may be recognized whether oral or in writing. In re Raven Marine, Inc. , 217 USPQ 68, 69 (TTAB 1983).

If the application indicates that use of the mark is pursuant to a license or franchise agreement, and the record contains nothing that contradicts the assertion of ownership by the applicant (i.e., the licensor or franchisor), the examining attorney will not inquire about the relationship between the applicant and the related company (i.e., the licensee or franchisee).

Ownership rights in a trademark or service mark may be acquired and maintained through the use of the mark by a controlled licensee even when the only use of the mark has been made, and is being made, by the licensee. Turner v. HMH Publ’g Co., 380 F.2d 224, 229, 154 USPQ 330, 334 (5th Cir. 1967), cert. denied, 389 U.S. 1006, 156 USPQ 720 (1967); Cent. Fid. Banks, Inc. v. First Bankers Corp. of Fla. , 225 USPQ 438, 440 (TTAB 1984) (holding that use of the mark by petitioner’s affiliated banks considered to inure to the benefit of petitioner bank holding company, even though the bank holding company could not legally render banking services and, thus, could not use the mark). However, a mere licensee cannot rely on use of the mark by the licensor, whether through the license or otherwise, to establish priority. Moreno v. Pro Boxing Supplies, Inc., 124 USPQ2d 1028, 1036 (TTAB 2017).

Joint applicants enjoy rights of ownership to the same extent as any other “person” who has a proprietary interest in a mark. Therefore, joint applicants may license others to use a mark and, by exercising sufficient control and supervision of the nature and quality of the goods or services to which the mark is applied, the joint applicants/licensors may claim the benefits of the use by the related company/licensee. In re Diamond Walnut Growers, Inc. and Sunsweet Growers Inc. , 204 USPQ 507, 510 (TTAB 1979) .

Stores that are operating under franchise agreements from another party are considered “related companies” of that party, and use of the mark by the franchisee/store inures to the benefit of the franchisor. Mr. Rooter Corp. v. Morris, 188 USPQ 392, 394 (E.D. La. 1975); Southland Corp. v. Schubert, 297 F. Supp. 477, 160 USPQ 375, 381 (C.D. Cal. 1968).

In all franchise and license situations, the key to ownership is the nature and extent of the control by the applicant over the goods or services to which the mark is applied. A trademark owner who fails to exercise sufficient control over licensees or franchisees may be found to have abandoned its rights in the mark. See Hurricane Fence Co. v. A-1 Hurricane Fence Co., 468 F. Supp. 975, 986; 208 USPQ 314, 325 (S.D. Ala. 1979).

In general, where the application states that a mark is used by a licensee or franchisee, the USPTO does not require an explanation of how the applicant controls the use.

1201.04 Inquiry Regarding Parties Named on Specimens or Elsewhere in Record

The USPTO does not inquire about the relationship between the applicant and other parties named on the specimen or elsewhere in the record, except when the reference to another party clearly contradicts the applicant’s verified statement that it is the owner of the mark or entitled to use the mark.

The examining attorney should inquire about another party if the record specifically states that another party is the owner of the mark, or if the record specifically identifies the applicant in a manner that contradicts the claim of ownership, for example, as a licensee. In these circumstances, registration should be refused under §1 of the Trademark Act, on the ground that the applicant is not the owner of the mark. Similarly, when the record indicates that the applicant is a United States distributor, importer, or other distributing agent for a foreign manufacturer, the examining attorney should require the applicant to establish its ownership rights in the United States in accordance with TMEP §1201.06(a) .

Where the specimen of use indicates that the goods are manufactured in a country other than the applicant’s home country, the examining attorney normally should not inquire whether the mark is used by a foreign manufacturer. See TMEP §1201.06(b) . Also, where the application states that use of the mark is by related companies, an explanation of how the applicant controls use of the mark by the related companies is not required. See TMEP §1201.03(a) .

1201.05 Acceptable Claim of Ownership Based on Applicant’s Own Use

An applicant’s claim of ownership of a mark may be based on the applicant’s own use of the mark, even though there is also use by a related company. The applicant is the owner by virtue of the applicant’s own use, and the application does not have to refer to use by a related company.

An applicant may claim ownership of a mark when the mark is applied on the applicant’s instruction. For example, if the applicant contracts with another party to have goods produced for the applicant and instructs the party to place the mark on the goods, that is considered the equivalent of the applicant itself placing the mark on its own goods and reference to related-company use is not necessary.

1201.06 Special Situations Pertaining to Ownership

1201.06(a) Applicant Is Merely Distributor or Importer

A distributor, importer, or other distributing agent of the goods of a manufacturer or producer does not acquire a right of ownership in the manufacturer’s or producer’s mark merely because it moves the goods in trade. See In re Bee Pollen from Eng. Ltd. , 219 USPQ 163 (TTAB 1983); Audioson Vertriebs – GmbH v. Kirksaeter Audiosonics, Inc. , 196 USPQ 453 (TTAB 1977); Jean D’Albret v. Henkel-Khasana G.m.b.H. , 185 USPQ 317 (TTAB 1975); In re Lettmann,183 USPQ 369 (TTAB 1974); Bakker v. Steel Nurse of America Inc. , 176 USPQ 447 (TTAB 1972). A party that merely distributes goods bearing the mark of a manufacturer or producer is neither the owner nor a related-company user of the mark.

If the applicant merely distributes or imports goods for the owner of the mark, registration must be refused under §1 of the Trademark Act, except in the following situations:

- (1) If a parent and wholly owned subsidiary relationship exists between the distributor and the manufacturer, then the applicant’s statement that such a relationship exists disposes of an ownership issue. See TMEP §1201.03(b) .

- (2) If an applicant is the United States importer or distribution agent for a foreign manufacturer, then the applicant can register the foreign manufacturer’s mark in the United States, if the applicant submits one of the following:

- (a) written consent from the owner of the mark to registration in the applicant’s name, or

- (b) written agreement or acknowledgment between the parties that the importer or distributor is the owner of the mark in the United States, or

- (c) an assignment (or true copy) to the applicant of the owner’s rights in the mark as to the United States together with the business and good will appurtenant thereto.

See In re Pharmacia Inc., 2 USPQ2d 1883 (TTAB 1987); In re Geo. J. Ball, Inc., 153 USPQ 426 (TTAB 1967).

The Board has also found that a mere licensee cannot rely on the licensor’s use to prove priority. Moreno v. Pro Boxing Supplies, Inc. , 124 USPQ2d 1028, 1036 (TTAB 2017).

1201.06(b) Goods Manufactured in a Country Other than Where Applicant Is Located

Where a specimen indicates that the goods are manufactured in a country other than the applicant’s home country, the examining attorney normally should not inquire whether the mark is used by a foreign manufacturer. If, however, information in the record clearly contradicts the applicant’s verified claim of ownership (e.g., a statement in the record that the mark is owned by the foreign manufacturer and that the applicant is only an importer or distributor), then registration must be refused under §1, 15 U.S.C. §1051 , unless registration in the United States by the applicant is supported by the applicant’s submission of one of the documents listed in TMEP §1201.06(a) .

1201.06(c) Applicant Using Designation of a U.S. Government Agency or Instrumentality

For a mark that would otherwise be subject to a refusal under §2(a) because it falsely suggests a connection with a designation of a U.S. government agency, instrumentality, or program, such as names, acronyms, titles, terms, and symbols, but the record demonstrates that the applicant has some affiliation with the agency or program, the examining attorney must issue an information request under 37 C.F.R. §2.61(b) requiring further information as to ownership of the designation and authorization to register. If it appears that the applicant lacks authorization to register the designation in the mark, the examining attorney may refuse to register under §1 of the Trademark Act because the applicant is not the owner of the governmental designation in the mark. The mark may also be refused under §2(a) for false suggestion of a connection and under §§1 and 45 when such marks are the subject of statutory protection. See TMEP §1203.03(b)(ii) for refusals under false association for Government Agencies and Instrumentalities, TMEP §1205.01 for information about statutorily protected matter, and Appendix C for a non-exhaustive list of U.S. statutes protecting designations of certain government agencies and instrumentalities.

Disclaiming the name of, or acronym for, the U.S. government agency or instrumentality to which the mark refers generally will not overcome the refusal under §§1 and 45. See TMEP §1213.03(a) regarding unregistrable components of marks.

1201.07 Related Companies and Likelihood of Confusion

1201.07(a) “Single Source” – “Unity of Control”

Section 2(d) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1052(d) , requires that the examining attorney refuse registration when an applicant’s mark, as applied to the specified goods or services, so resembles a registered mark as to be likely to cause confusion. In general, registration of confusingly similar marks to separate legal entities is barred by §2(d). See TMEP §§1207–1207.01(d)(xi) . However, the Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit has held that, where the applicant is related in ownership to a company that owns a registered mark that would otherwise give rise to a likelihood of confusion, the examining attorney must consider whether, in view of all the circumstances, use of the mark by the applicant is likely to confuse the public about the source of the applicant’s goods because of the resemblance of the applicant’s mark to the mark of the other company. The Court stated that:

The question is whether, despite the similarity of the marks and the goods on which they are used, the public is likely to be confused about the source of the hair straightening products carrying the trademark “WELLASTRATE.” In other words, is the public likely to believe that the source of the product is Wella U.S. rather than the German company or the Wella organization.

In re Wella A.G., 787 F.2d 1549, 1552, 229 USPQ 274, 276 (Fed. Cir. 1986); cf. In re Wacker Neuson SE,97 USPQ2d 1408 (TTAB 2010) (finding that the record made clear that the parties were related and that the goods and services were provided by the applicant).

The Wella Court remanded the case to the Board for consideration of the likelihood of confusion issue. In ruling on that issue, the Board concluded that there was no likelihood of confusion, stating as follows:

[A] determination must be made as to whether there exists a likelihood of confusion as to source, that is, whether purchasers would believe that particular goods or services emanate from a single source, when in fact those goods or services emanate from more than a single source. Clearly, the Court views the concept of “source” as encompassing more than “legal entity.” Thus, in this case, we are required to determine whether Wella A.G. and Wella U.S. are the same source or different sources . . . .

The existence of a related company relationship between Wella U.S. and Wella A.G. is not, in itself, a basis for finding that any “WELLA” product emanating from either of the two companies emanates from the same source. Besides the existence of a legal relationship, there must also be a unity of control over the use of the trademarks. “Control” and “source” are inextricably linked. If, notwithstanding the legal relationship between entities, each entity exclusively controls the nature and quality of the goods to which it applies one or more of the various “WELLA” trademarks, the two entities are in fact separate sources. Wella A.G. has made of record a declaration of the executive vice president of Wella U.S., which declaration states that Wella A.G. owns substantially all the outstanding stock of Wella U.S. and “thus controls the activities and operations of Wella U.S., including the selection, adoption and use of the trademarks.” While the declaration contains no details of how this control is exercised, the declaration is sufficient, absent contradictory evidence in the record, to establish that control over the use of all the “WELLA” trademarks in the United States resides in a single source.

In re Wella A.G. , 5 USPQ2d 1359, 1361 (TTAB 1987) (emphasis in original), rev’d on other grounds, 858 F.2d 725, 8 USPQ2d 1365 (Fed. Cir. 1988).

Therefore, in some limited circumstances, the close relationship between related companies will obviate any likelihood of confusion in the public mind because the related companies constitute a single source. See TMEP §§1201.07(b)-1201.07(b)(iv) for further information.

1201.07(b) Appropriate Action with Respect to Assertion of Unity of Control

First, it is important to note that analysis under Wella is not triggered until an applicant affirmatively asserts that a §2(d) refusal is inappropriate because the applicant and the registrant, though separate legal entities, constitute a single source, or the applicant raises an equivalent argument. Examining attorneys should issue §2(d) refusals in any case where an analysis of the marks and the goods or services of the respective parties indicates a bar to registration under §2(d). The examining attorney should not attempt to analyze the relationship between an applicant and registrant until an applicant, in some form, relies on the nature of the relationship to obviate a refusal under §2(d).

Once an applicant has made this assertion, the question is whether the specific relationship is such that the two entities constitute a “single source,” so that there is no likelihood of confusion. The following guidelines may assist the examining attorney in resolving questions of likelihood of confusion when the marks are owned by related companies and the applicant asserts unity of control. (In many of these situations, the applicant may choose to attempt to overcome the §2(d) refusal by submitting a consent agreement or other conventional evidence to establish no likelihood of confusion. See TMEP §1207.01(d) . Another way to overcome a §2(d) refusal is to assign all relevant registrations to the same party.)

1201.07(b)(i) When Either Applicant or Registrant Owns All of the Other Entity

If the applicant or the applicant’s attorney represents that either the applicant or the registrant owns all of the other entity, and there is no contradictory evidence, then the examining attorney should conclude that there is unity of control, a single source, and no likelihood of confusion. This would apply to an individual who owns all the stock of a corporation, and to a corporation and a wholly owned subsidiary or a subsidiary of a wholly owned subsidiary. In this circumstance, additional representations or declarations should generally not be required, absent contradictory evidence.

1201.07(b)(ii) Joint Ownership or Ownership of Substantially All of the Other Entity

Either Applicant or Registrant Owns Substantially All of the Other Entity . In Wella, the applicant provided a declaration stating that the applicant owned substantially all of the stock of the registrant and that the applicant thus controlled the activities of the registrant, including the selection, adoption, and use of trademarks. In re Wella A.G., 5 USPQ2d 1359, 1361 (TTAB 1987) , rev’d on other grounds, 858 F.2d 725, 8 USPQ2d 1365 (Fed. Cir. 1988). The Board concluded that this declaration alone, absent contradictory evidence, established unity of control, a single source, and no likelihood of confusion. Id. Therefore, if either the applicant or the registrant owns substantially all of the other entity and asserts control over the activities of the other entity, including its trademarks, and there is no contradictory evidence, the examining attorney should conclude that unity of control is present, that the entities constitute a single source, and that there is no likelihood of confusion under §2(d). In such a case, the applicant should generally provide these assertions in the form of an affidavit or declaration under 37 C.F.R. §2.20 .

Joint Ownership. The examining attorney may also accept an applicant’s assertion of unity of control when the applicant is shown in USPTO records as a joint owner of the cited registration, or the owner of the registration is listed as a joint owner of the application, and the applicant submits a written statement asserting control over the use of the mark by virtue of joint ownership, if there is no contradictory evidence.

1201.07(b)(iii) When the Record Does Not Support a Presumption of Unity of Control

If neither the applicant nor the registrant owns all or substantially all of the other entity, and USPTO records do not show their joint ownership of the application or cited registration ( see TMEP §1201.07(b)(ii) ), the applicant bears a more substantial burden to establish that unity of control is present. For instance, if both the applicant and the registrant are wholly owned by a third common parent, the applicant would have to provide detailed evidence to establish how one sister corporation controlled the trademark activities of the other to establish unity of control to support the contention that the sister corporations constitute a single source. See In re Pharmacia Inc. , 2 USPQ2d 1883 (TTAB 1987); Greyhound Corp. v. Armour Life Ins. Co. , 214 USPQ 473 (TTAB 1982). Likewise, where an applicant and registrant have certain stockholders, directors, or officers in common, the applicant must demonstrate with detailed evidence or explanation how those relationships establish unity of control. See Pneutek, Inc. v. Scherr, 211 USPQ 824 (TTAB 1981). The applicant’s evidence or explanation should generally be supported by an affidavit or a declaration under 37 C.F.R. §2.20 .

1201.07(b)(iv) When the Record Contradicts an Assertion of Unity of Control

In contrast to those circumstances where the relationship between the parties may support a presumption of unity of control or at least afford an applicant the opportunity to demonstrate unity of control, some relationships, by their very nature, contradict any claim that unity of control is present. For instance, if the relationship between the parties is that of licensor and licensee, unity of control will ordinarily not be present. The licensing relationship suggests ownership in one party and control by that one party over only the use of a specific mark or marks, but not over the operations or activities of the licensee generally. Thus, there is no unity of control and no basis for concluding that the two parties form a single source. Precisely because unity of control is absent, a licensing agreement is necessary. The licensing agreement enables the licensor/owner to control specific activities to protect its interests as the sole source or sponsor of the goods or services provided under the mark. Therefore, in these situations, it is most unlikely that an applicant could establish unity of control to overcome a §2(d) refusal.

1202 Use of Subject Matter as Trademark

In an application under §1 of the Act, the examining attorney must determine whether the subject matter for which registration is sought is used as a trademark by reviewing all evidence (e.g., the specimen and any promotional material) of record in the application. See In re Safariland Hunting Corp ., 24 USPQ2d 1380, 1381 (TTAB 1992) (examining attorney should look primarily to the specimen to determine whether a designation would be perceived as a source indicator, but may also consider other evidence, if there is other evidence of record).

Not everything that a party adopts and uses with the intent that it function as a trademark necessarily achieves this goal or is legally capable of doing so, and not everything that is recognized or associated with a party is necessarily a registrable trademark. As the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals observed in In re The Standard Oil Co., 275 F.2d 945, 947, 125 USPQ 227, 229 (C.C.P.A. 1960):

The Trademark Act is not an act to register words but to register trademarks. Before there can be registrability, there must be a trademark (or a service mark) and, unless words have been so used, they cannot qualify for registration. Words are not registrable merely because they do not happen to be descriptive of the goods or services with which they are associated.

Sections 1 and 2 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §§1051 and 1052 , require that the subject matter presented for registration be a “trademark.” Section 45 of the Act, 15 U.S.C. §1127 , defines that term as follows:

The term “trademark” includes any word, name, symbol, or device, or any combination thereof–

- (1) used by a person, or

- (2) which a person has a bona fide intention to use in commerce and applies to register on the principal register established by this Act,

to identify and distinguish his or her goods, including a unique product, from those manufactured or sold by others and to indicate the source of the goods, even if that source is unknown.

Thus, §§1, 2, and 45 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §§1051 , 1052 , and 1127 , provide the statutory basis for refusal to register on the Principal Register subject matter that, due to its inherent nature or the manner in which it is used, does not function as a mark to identify and distinguish the applicant’s goods. The statutory basis for refusal of registration on the Supplemental Register of matter that does not function as a trademark is §§23(c) and 45 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §§1091(c) , 1127 .

When the examining attorney refuses registration on the ground that the subject matter is not used as a trademark, the examining attorney must explain the specific reason for the conclusion that the subject matter is not used as a trademark. See TMEP §§1202.01–1202.19 for a discussion of situations in which it may be appropriate, depending on the circumstances, for the examining attorney to refuse registration on the ground that the proposed mark does not function as a trademark, e.g., TMEP §§1202.01 (trade names), 1202.02(a)–1202.02(a)(viii) (functionality), 1202.03–1202.03(g) (ornamentation), 1202.04 (informational matter), 1202.05–1202.05(i) (color marks), 1202.06–1202.06(c) (goods in trade), 1202.07–1202.07(b) (columns or sections of publications), 1202.08–1202.08(f) (title of single creative work), 1202.09–1202.09(b) (names of artists and authors), 1202.11 (background designs and shapes), 1202.12 (varietal and cultivar names), 1202.16 (model or grade designations), 1202.17 (universal symbols), 1202.18 (hashtags), and 1202.19 (repeating patterns).

The presence of the letters “SM” or “TM” cannot transform an otherwise unregistrable designation into a registrable mark. In re Remington Prods. Inc ., 3 USPQ2d 1714, 1715 (TTAB 1987); In re Anchor Hocking Corp ., 223 USPQ 85, 88 (TTAB 1984); In re Minnetonka, Inc ., 212 USPQ 772, 779 n.12 (TTAB 1981).

The issue of whether a designation functions as a mark usually is tied to the use of the mark, as evidenced by the specimen. Therefore, unless the drawing and description of the mark are dispositive of the failure to function without the need to consider a specimen, generally, no refusal on this basis will be issued in an intent-to-use application under §1(b) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1051(b) , until the applicant has submitted a specimen(s) with an allegation of use (i.e., either an amendment to allege use under 15 U.S.C. §1051(c) or a statement of use under 15 U.S.C. §1051(d) ). However, in a §1(b) application for which no specimen has been submitted, if the examining attorney anticipates that a refusal will be made on the ground that the matter presented for registration does not function as a mark, the potential refusal should be brought to the applicant’s attention in the first Office action. This is done strictly as a courtesy. If information regarding this possible ground for refusal is not provided to the applicant before the allegation of use is filed, the USPTO is not precluded from refusing registration on this basis.

In an application under §44 or §66(a), where a specimen of use is not required prior to registration, it is appropriate for the examining attorney to issue a failure to function refusal where the mark on its face, as shown on the drawing and described in the description, reflects a failure to function. See In re Right-On Co., 87 USPQ2d 1152, 1156-57 (TTAB 2008) (noting the propriety of and affirming an ornamentation refusal in a §66(a) application).

See TMEP §§1301.02–1301.02(f) regarding use of subject matter as a service mark; TMEP §§1302-1305 regarding use of subject matter as a collective mark; and TMEP §§1306-1306.06(c) regarding use of subject matter as a certification mark.

1202.01 Refusal of Matter Used Solely as a Trade Name

The name of a business or company is a trade name. The Trademark Act distinguishes trade names from trademarks and service marks by definition. While a trademark is used to identify and distinguish the trademark owner’s goods from those manufactured or sold by others and to indicate the source of the goods, “trade name” and “commercial name” are defined in §45 of the Act, 15 U.S.C. §1127 , as follows:

The terms “trade name” and “commercial name” mean any name used by a person to identify his or her business or vocation.

The Trademark Act does not provide for registration of trade names. See In re Letica Corp., 226 USPQ 276, 277 (TTAB 1985) (“[T]here was a clear intention by the Congress to draw a line between indicia which perform only trade name functions and indicia which perform or also perform the function of trademarks or service marks.”).

If the examining attorney determines that matter for which registration is requested is merely a trade name, registration must be refused both on the Principal Register and on the Supplemental Register. The statutory basis for refusal of trademark registration on the ground that the matter is used merely as a trade name is §§1, 2, and 45 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §§1051 , 1052 , and 1127 , and, in the case of matter sought to be registered for services, §§1, 2, 3, and 45, 15 U.S.C. §§1051 , 1052 , 1053 , and 1127 .

A designation may function as both a trade name and a trademark or service mark. See In re Walker Process Equip. Inc., 233 F.2d 329, 332, 110 USPQ 41, 43 (C.C.P.A. 1956), aff’g 102 USPQ 443 (Comm’r Pats. 1954).

If subject matter presented for registration in an application is a trade name or part of a trade name, the examining attorney must determine whether it is also used as a trademark or service mark, by examining the specimen and other evidence of record in the application file. See In re Diamond Hill Farms , 32 USPQ2d 1383, 1384 (TTAB 1994) (holding that DIAMOND HILL FARMS, as used on containers for goods, is a trade name that identifies applicant as a business entity rather than a mark that identifies applicant’s goods and distinguishes them from those of others).

Whether matter that is a trade name (or a portion thereof) also performs the function of a trademark depends on the manner of its use and the probable impact of the use on customers. See In re Supply Guys, Inc. , 86 USPQ2d 1488, 1491 (TTAB 2008) (finding that the use of trade name in “Ship From” section of Federal Express label where it serves as a return address does not demonstrate trademark use as the term appears where customers would look for the name of the party shipping the package); In re Unclaimed Salvage & Freight Co., 192 USPQ 165, 168 (TTAB 1976) (“It is our opinion that the foregoing material reflects use by applicant of the notation ‘UNCLAIMED SALVAGE & FREIGHT CO.’ merely as a commercial, business, or trade name serving to identify applicant as a viable business entity; and that this is or would be the general and likely impact of such use upon the average person encountering this material under normal circumstances and conditions surrounding the distribution thereof.”); In re Lytle Eng’g & Mfg. Co. , 125 USPQ 308 (TTAB 1960) (“‘LYTLE’ is applied to the container for applicant’s goods in a style of lettering distinctly different from the other portion of the trade name and is of such nature and prominence that it creates a separate and independent impression.”).

The presence of an entity designator in a name sought to be registered and the proximity of an address are both factors to be considered in determining whether a proposed mark is merely a trade name. In re Univar Corp. , 20 USPQ2d 1865, 1869 (TTAB 1991) (“[T]he mark “UNIVAR” independently projects a separate commercial impression, due to its presentation in a distinctively bolder, larger and different type of lettering and, in some instances, its additional use in a contrasting color, and thus does more than merely convey information about a corporate relationship.”); see also Book Craft, Inc. v. BookCrafters USA, Inc. , 222 USPQ 724, 727 (TTAB 1984) (“That the invoices . . . plainly show . . . service mark use is apparent from the fact that, not only do the words ‘BookCrafters, Inc.’ appear in larger letters and a different style of print than the address, but they are accompanied by a design feature (the circularly enclosed ends of two books).”).

A determination of whether matter serves solely as a trade name rather than as a mark requires consideration of the way the mark is used, as evidenced by the specimen(s). Therefore, no refusal on that ground will be issued in an intent-to-use application under §1(b) until the applicant has submitted specimen(s) of use in conjunction with an allegation of use under 15 U.S.C. §1051(c) or 15 U.S.C. §1051(d) .

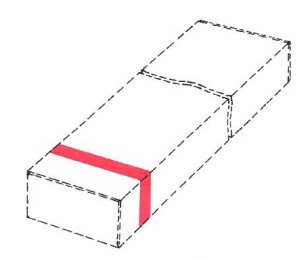

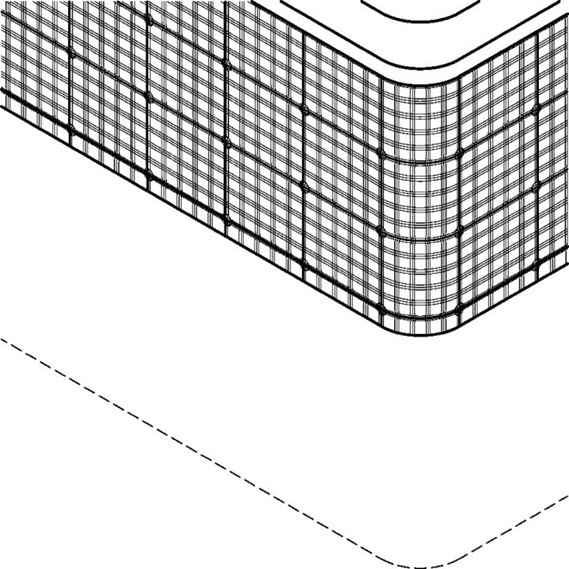

1202.02 Registration of Trade Dress

Trade dress constitutes a “symbol” or “device” within the meaning of §2 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1052 . Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros. , 529 U.S. 205, 209-210, 54 USPQ2d 1065, 1065-66 (2000). Trade dress originally included only the packaging or “dressing” of a product, but in recent years has been expanded to encompass the design of a product. It is usually defined as the “total image and overall appearance” of a product, or the totality of the elements, and “may include features such as size, shape, color or color combinations, texture, graphics.” Two Pesos, Inc. v. Taco Cabana, Inc. , 505 U.S. 763, 764 n.1, 23 USPQ2d 1081, 1082 n.1 (1992).

Thus, trade dress includes the design of a product (i.e., the product shape or configuration), the packaging in which a product is sold (i.e., the “dressing” of a product), the color of a product or of the packaging in which a product is sold, and the flavor of a product. Wal-Mart, 529 U.S. at 205, 54 USPQ2d at 1065 (design of children’s outfits constitutes product design); Two Pesos, 505 U.S. at 763, 23 USPQ2d at 1081 (interior of a restaurant is akin to product packaging); Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Prods. Co. , 514 U.S. 159, 34 USPQ2d 1161 (1995) (color alone may be protectible); In re N.V. Organon , 79 USPQ2d 1639 (TTAB 2006) (flavor is analogous to product design and may be protectible unless it is functional). However, this is not an exhaustive list, because “almost anything at all that is capable of carrying meaning” may be used as a “symbol” or “device” and constitute trade dress that identifies the source or origin of a product. Qualitex, 514 U.S. at 162, 34 USPQ2d at 1162. When it is difficult to determine whether the proposed mark is product packaging or product design, such “ambiguous” trade dress is treated as product design. Wal-Mart, 529 U.S. at 215, 54 USPQ2d at 1066. Trade dress marks may be used in connection with goods and services.

In some cases, the nature of a potential trade dress mark may not be readily apparent. A determination of whether the mark constitutes trade dress must be informed by the application content, including the drawing, the description of the mark, the identification of goods or services, and the specimen, if any. If it remains unclear whether the proposed mark constitutes trade dress, the examining attorney may call or e-mail the applicant to clarify the nature of the mark, or issue an Office action requiring information regarding the nature of the mark, as well as any other necessary clarifications, such as a clear drawing and an accurate description of the mark. 37 C.F.R. §2.61(b) . The applicant’s response would then confirm whether the proposed mark is trade dress.

When an applicant applies to register a product design, product packaging, color, or other trade dress for goods or services, the examining attorney must separately consider two substantive issues: (1) functionality; and (2) distinctiveness. See TrafFix Devices, Inc. v. Mktg.Displays, Inc ., 532 U.S. 23, 28-29, 58 USPQ2d 1001, 1004-1005 (2001); Two Pesos, 505 U.S. at 775, 23 USPQ2d at 1086; In re Morton-Norwich Prods., Inc. , 671 F.2d 1332, 1343, 213 USPQ 9, 17 (C.C.P.A. 1982) . See TMEP §§1202.02(a)–1202.02(a)(viii) regarding functionality and 1202.02(b)–1202.02(b)(ii) and 1212–1212.10 regarding distinctiveness. In many cases, a refusal of registration may be necessary on both grounds. In any application where a product design is refused because it is functional, registration must also be refused on the ground that the proposed mark is nondistinctive because product design is never inherently distinctive. However, since product packaging may be inherently distinctive, in an application where product packaging is refused as functional, registration should also be refused on the ground that the proposed mark is nondistinctive. Even if it is ultimately determined that the product packaging is not functional, the alternative basis for refusal may stand.

If a proposed trade dress mark is ultimately determined to be functional, claims and evidence that the mark has acquired distinctiveness or secondary meaning are irrelevant and registration will be refused. TrafFix , 532 U.S. at 33, 58 USPQ2d at 1007.

With respect to the functionality and distinctiveness issues in the specific context of color as a mark, see TMEP §1202.05(a) and (b) .

1202.02(a) Functionality of Trade Dress

In general terms, trade dress is functional, and cannot serve as a trademark, if a feature of that trade dress is “essential to the use or purpose of the article or if it affects the cost or quality of the article.” Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Prods. Co., 514 U.S. 159, 165, 34 USPQ2d 1161, 1163-64 (1995) (quoting Inwood Labs., Inc. v. Ives Labs., Inc. , 456 U.S. 844, 850, n.10, 214 USPQ 1, 4, n.10 (1982)).

1202.02(a)(i) Statutory Basis for Functionality Refusal

Before October 30, 1998, there was no specific statutory reference to functionality as a ground for refusal, and functionality refusals were thus issued as failure-to-function refusals under §§1, 2, and 45 of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §§1051 , 1052 , and 1127 .

Effective October 30, 1998, the Technical Corrections to Trademark Act of 1946, Pub. L. No. 105-330, §201, 112 Stat. 3064, 3069, amended the Trademark Act to expressly prohibit registration on either the Principal or Supplemental Register of functional matter:

- Section 2(e)(5) of the Trademark Act, 15 U.S.C. §1052(e)(5) , prohibits registration on the Principal Register of “matter that, as a whole, is functional.”

- Section 2(f) of the Act, 15 U.S.C. §1052(f) , provides that matter that, as a whole, is functional may not be registered even on a showing that it has become distinctive.

- Section 23(c) of the Act, 15 U.S.C. §1091(c) , provides that a mark that, as a whole, is functional may not be registered on the Supplemental Register.

- Section 14(3) of the Act, 15 U.S.C. §1064(3) , lists functionality as a ground that can be raised in a cancellation proceeding more than five years after the date of registration.

- Section 33(b)(8) of the Act, 15 U.S.C. §1115(b)(8) , lists functionality as a statutory defense to infringement in a suit involving an incontestable registration.

These amendments codified case law and the longstanding USPTO practice of refusing registration of functional matter.

1202.02(a)(ii) Purpose of Functionality Doctrine

The functionality doctrine, which prohibits registration of functional product features, is intended to encourage legitimate competition by maintaining a proper balance between trademark law and patent law. As the Supreme Court explained, in Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Prods. Co. , 514 U.S. 159, 164-165, 34 USPQ2d 1161, 1163 (1995):

The functionality doctrine prevents trademark law, which seeks to promote competition by protecting a firm’s reputation, from instead inhibiting legitimate competition by allowing a producer to control a useful product feature. It is the province of patent law, not trademark law, to encourage invention by granting inventors a monopoly over new product designs or functions for a limited time, 35 U.S.C. Sections 154, 173, after which competitors are free to use the innovation. If a product’s functional features could be used as trademarks, however, a monopoly over such features could be obtained without regard to whether they qualify as patents and could be extended forever (because trademarks may be renewed in perpetuity).

In other words, the functionality doctrine ensures that protection for utilitarian product features be properly sought through a limited-duration utility patent, and not through the potentially unlimited protection of a trademark registration. Upon expiration of a utility patent, the invention covered by the patent enters the public domain, and the functional features disclosed in the patent may then be copied by others – thus encouraging advances in product design and manufacture. In TrafFix Devices, Inc. v. Mktg. Displays, Inc. , 532 U.S. 23, 34-35, 58 USPQ2d 1001, 1007 (2001), the Supreme Court reiterated this rationale, also noting that the functionality doctrine is not affected by evidence of acquired distinctiveness.

Thus, even when the evidence establishes that consumers have come to associate a functional product feature with a single source, trademark protection will not be granted in light of the public policy reasons stated. Id.

1202.02(a)(iii) Background and Definitions

1202.02(a)(iii)(A) Functionality

Functional matter cannot be protected as a trademark. 15 U.S.C. §§1052(e)(5) and (f) , 1064(3) , 1091(c) , and 1115(b) . A feature is functional as a matter of law if it is “essential to the use or purpose of the article or if it affects the cost or quality of the article.” TrafFix Devices, Inc. v. Mktg. Displays, Inc. , 532 U.S. 23, 33, 58 USPQ2d 1001, 1006 (2001); Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Prods. Co., 514 U.S. 159, 165, 34 USPQ2d 1161, 1163-64 (1995); Inwood Labs., Inc. v. Ives Labs., Inc., 456 U.S. 844, 850, n.10, 214 USPQ 1, 4, n.10 (1982).

While some courts had developed a definition of functionality that focused solely on “competitive need” – thus finding a particular product feature functional only if competitors needed to copy that design in order to compete effectively – the Supreme Court held that this “was incorrect as a comprehensive definition” of functionality. TrafFix, 532 U.S. at 33, 58 USPQ2d at 1006. The Court emphasized that where a product feature meets the traditional functionality definition – that is, it is essential to the use or purpose of the product or affects its cost or quality – then the feature is functional, regardless of the availability to competitors of other alternatives. Id.; see also Valu Eng’g, Inc. v. Rexnord Corp., 278 F.3d 1268, 1276, 61 USPQ2d 1422, 1427 (Fed. Cir. 2002) (“Rather, we conclude that the [ TrafFix] Court merely noted that once a product feature is found functional based on other considerations there is no need to consider the availability of alternative designs, because the feature cannot be given trade dress protection merely because there are alternative designs available” (footnote omitted).)

However, since the preservation of competition is an important policy underlying the functionality doctrine, competitive need, although not determinative, remains a significant consideration in functionality determinations. Id. at 1278, 1428.

The determination that a proposed mark is functional constitutes, for public policy reasons, an absolute bar to registration on either the Principal or the Supplemental Register, regardless of evidence showing that the proposed mark has acquired distinctiveness. See TrafFix, 532 U.S. at 29-33, 58 USPQ2d at 1005-1007; see also In re Controls Corp. of Am. , 46 USPQ2d 1308, 1312 (TTAB 1998) (rejecting applicant’s claim that “registration on the Supplemental Register of a de jure functional configuration is permissible if the design is ‘capable’ of distinguishing applicant’s goods”). Thus, if an applicant responds to a functionality refusal under §2(e)(5), 15 U.S.C. §1052(e)(5) , by submitting an amendment seeking registration on the Supplemental Register that is not made in the alternative, such an amendment does not introduce a new issue warranting a nonfinal Office action. See TMEP §714.05(a)(i) . Instead, the functionality refusal must be maintained and made final, if appropriate, under §§23(c) and 45, 15 U.S.C. §§1091(c) , 1127 , as that is the statutory authority governing a functionality refusal on the Supplemental Register. Additionally, for functionality refusals, the associated nondistinctiveness refusal must be withdrawn. See In re Heatcon, Inc. , 116 USPQ2d 1366, 1370 (TTAB 2015) .

See TMEP §§1202.02(a)(v)–1202.02(a)(v)(D) regarding evidentiary considerations pertaining to functionality refusals.

1202.02(a)(iii)(B) “De Jure” and “De Facto” Functionality

Prior to 2002, the USPTO used the terms “ de facto” and “ de jure” in assessing whether “subject matter” (usually a product feature or the configuration of the goods) presented for registration was functional. This distinction originated with the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals’ decision in In re Morton-Norwich Prods., Inc., 671 F.2d 1332, 213 USPQ 9 (C.C.P.A. 1982), which was discussed by the Federal Circuit in Valu Eng’g, Inc. v. Rexnord Corp., 278 F.3d 1268, 1274, 61 USPQ2d 1422, 1425 (Fed. Cir. 2002):

Our decisions distinguish de facto functional features, which may be entitled to trademark protection, from de jure functional features, which are not. ‘In essence, de facto functional means that the design of a product has a function, i.e., a bottle of any design holds fluid.’ In re R.M. Smith, Inc., 734 F.2d 1482, 1484, 222 USPQ 1, 3 (Fed. Cir. 1984). De facto functionality does not necessarily defeat registrability. Morton-Norwich, 671 F.2d at 1337, 213 USPQ at 13 (A design that is de facto functional, i.e., ‘functional’ in the lay sense . . . may be legally recognized as an indication of source.’). De jure functionality means that the product has a particular shape ‘because it works better in this shape.’ Smith, 734 F.2d at 1484, 222 USPQ at 3.

However, in three Supreme Court decisions involving functionality – TrafFix Devices, Inc. v. Mktg. Displays, Inc., 532 U.S. 23, 58 USPQ2d 1001 (2001), Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros., 529 U.S. 205, 54 USPQ2d 1065 (2000), and Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Prods. Co. , 514 U.S. 159, 34 USPQ2d 1161 (1995) – the Court did not use the “ de facto/de jure” distinction. Nor were these terms used when the Trademark Act was amended to expressly prohibit registration of matter that is “functional.” Technical Corrections to Trademark Act of 1946, Pub. L. No. 105-330, §201, 112 Stat. 3064, 3069 (1998). Accordingly, in general, examining attorneys no longer make this distinction in Office actions that refuse registration based on functionality.

De facto functionality is not a ground for refusal. In re Ennco Display Sys. Inc. , 56 USPQ2d 1279, 1282 (TTAB 2000) ; In re Parkway Mach. Corp ., 52 USPQ2d 1628, 1631 n.4 (TTAB 1999) .

1202.02(a)(iv) Burden of Proof in Functionality Determinations

The examining attorney must establish a prima facie case that the proposed trade dress mark sought to be registered is functional in order to make and maintain the §2(e)(5) functionality refusal. See In re Becton, Dickinson & Co., 675 F.3d 1368, 1374, 102 USPQ2d 1372, 1376 (Fed. Cir. 2012); Textron, Inc. v. U.S. Int’l Trade Comm’n, 753 F.2d 1019, 1025, 224 USPQ 625, 629 (Fed. Cir. 1985); In re R.M. Smith, Inc., 734 F.2d 1482, 1484, 222 USPQ 1, 3 (Fed. Cir. 1984). To do so, the examining attorney must not only examine the application content (i.e., the drawing, the description of the mark, the identification of goods or services, and the specimen, if any), but also conduct independent research to obtain evidentiary support for the refusal. In applications where there is reason to believe that the proposed mark may be functional, but the evidence is lacking to issue the §2(e)(5) refusal in the first Office action, a request for information pursuant to 37 C.F.R. §2.61(b) must be issued to obtain information from the applicant so that an informed decision about the validity of the functionality refusal can be made.

The burden then shifts to the applicant to present “competent evidence” to rebut the examining attorney’s prima facie case of functionality. See In re Becton, Dickinson & Co. , 675 F.3d at 1374, 102 USPQ2d at 1374; Textron, Inc. v. U.S. Int’l Trade Comm’n , 753 F.2d at 1025, 224 USPQ at 629; In re R.M. Smith, Inc., 734 F.2d at 1484, 222 USPQ at 3; In re Bio-Medicus Inc., 31 USPQ2d 1254, 1257 n.5 (TTAB 1993). The “competent evidence” standard requires proof by preponderant evidence. In re Becton, Dickinson & Co., 675 F.3d at 1374, 102 USPQ2d at 1377.

The functionality determination is a question of fact, and depends on the totality of the evidence presented in each particular case. In re Becton, Dickinson & Co., 675 F.3d at 1372, 102 USPQ2d at 1375; Valu Eng’g, Inc. v. Rexnord Corp. , 278 F.3d 1268, 1273, 61 USPQ2d 1422, 1424 (Fed. Cir. 2002); In re Udor U.S.A., Inc. , 89 USPQ2d 1978, 1979 (TTAB 2009); In re Caterpillar Inc. , 43 USPQ2d 1335, 1338 (TTAB 1997). While there is no set amount of evidence that an examining attorney must present to establish a prima facie case of functionality, it is clear that there must be evidentiary support for the refusal in the record. See, e.g., In re Morton-Norwich Prods., Inc. , 671 F.2d 1332, 1342, 213 USPQ 9, 16-17 (C.C.P.A. 1982) (admonishing both the examining attorney and the Board for failing to support the functionality determination with even “one iota of evidence”).

If the design sought to be registered as a mark is the subject of a utility patent that discloses the feature’s utilitarian advantages, the applicant bears an especially “heavy burden of showing that the feature is not functional” and “ overcoming the strong evidentiary inference of functionality.” TrafFix Devices, Inc. v. Mktg. Displays, Inc. , 532 U.S. 23, 30, 58 USPQ2d 1001, 1005 (2001); Udor U.S.A., Inc., 89 USPQ2d at 1979-80; see TMEP §1202.02(a)(v)(A) .

1202.02(a)(v) Evidence and Considerations Regarding Functionality Determinations

A determination of functionality normally involves consideration of one or more of the following factors, commonly known as the “ Morton-Norwich factors”:

- (1) the existence of a utility patent that discloses the utilitarian advantages of the design sought to be registered;

- (2) advertising by the applicant that touts the utilitarian advantages of the design;

- (3) facts pertaining to the availability of alternative designs; and

- (4) facts pertaining to whether the design results from a comparatively simple or inexpensive method of manufacture.

In re Becton, Dickinson & Co., 675 F.3d 1368, 1374-75, 102 USPQ2d 1372, 1377 (Fed. Cir. 2012); In re Morton-Norwich Prods., Inc. , 671 F.2d 1332, 1340-1341, 213 USPQ 9, 15-16 (C.C.P.A. 1982).

Since relevant technical information is often more readily available to an applicant, the applicant will often be the source of most of the evidence relied upon by the examining attorney in establishing a prima facie case of functionality in an ex parte case. In re Teledyne Indus. Inc., 696 F.2d 968, 971, 217 USPQ 9, 11 (Fed. Cir. 1982); In re Witco Corp. , 14 USPQ2d 1557, 1560 (TTAB 1989) . Therefore, in an application for a trade dress mark, when there is reason to believe that the proposed mark may be functional, the examining attorney must perform a search for evidence to support the Morton-Norwich factors. In applications where there is reason to believe that the proposed mark may be functional, the first Office action must include a request for information under 37 C.F.R. §2.61(b) , requiring the applicant to provide information necessary to permit an informed determination concerning the functionality of the proposed mark. See In re Babies Beat Inc. , 13 USPQ2d 1729, 1731 (TTAB 1990) (finding that registration is properly refused where applicant failed to comply with examining attorney’s request for copies of patent applications and other patent information). Such a request should be issued for most product design marks.

Accordingly, the examining attorney’s request for information should pertain to the Morton-Norwich factors and: (1) ask the applicant to provide copies of any patent(s) or any pending or abandoned patent application(s); (2) ask the applicant to provide any available advertising, promotional, or explanatory material concerning the goods/services, particularly any material specifically related to the features embodied in the proposed mark; (3) inquire of the applicant whether alternative designs are available; and (4) inquire whether the features sought to be registered make the product easier or cheaper to manufacture. The examining attorney should examine the specimen(s) for information relevant to the Morton-Norwich factors, and conduct independent research of applicant’s and competitors’ websites, industry practice and standards, and legal databases such as LexisNexis®. The examining attorney may also consult USPTO patent records.