eBook: Introduction to USPTO Trademark Prosecution

Alt Legal Team | May 15, 2024

This eBook was originally published on April 20, 2021. It has been continually updated, most recently as of May 15, 2024.

Introduction

This eBook will help you understand the substantive law behind trademarks and provide practical guidance when it comes to filing and successfully registering an application with the US Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). To begin, this eBook will guide you through the different types of Intellectual Property and give context for how trademarks fit in. Next, you’ll learn about trademark strength and why some marks are stronger and more easily registrable than others. Once you’ve gained an understanding of how trademarks function, you’ll learn about the timeline of a trademark application and what happens once it has been filed. Lastly, the eBook provides a comprehensive overview of the various types of roadblocks that you may encounter when filing a trademark application. This portion of the eBook will provide you with helpful guidance in selecting a strong, registrable trademark and will show you how to overcome the USPTO’s arguments against the mark. Overall, this eBook will give you the knowledge that you’ll need to tackle your first trademark filings with confidence.

Types of Intellectual Property

Intellectual Property (IP) is the umbrella term for three distinct types of IP: patents, copyrights, and trademarks. Practicing each type of IP requires specific knowledge and typically, IP attorneys will specialize in either “hard IP” (patent) or “soft IP” (trademark and copyright). Attorneys who file and prosecute patents must be admitted to the patent bar, which requires a scientific, technical background (usually an undergraduate degree in Biology, Chemistry, Engineering, Computer Science, or other related technical and/or scientific fields) as well as the completion of an entrance exam. As a result, not all attorneys may prosecute patents. Attorneys who specialize in trademarks and copyrights do not need a specific educational background, but they must have a keen understanding of branding, business, and marketing so that they can properly position their clients’ IP in the marketplace to obtain maximum IP protection. It is important to note that IP attorneys work very closely with paralegals who have developed expertise in IP law. Often, like IP attorneys, IP paralegals will specialize in a particular area within IP based on their educational background and/or experience. Alt Legal has developed a free Trademark Paralegal Course to help new and experienced trademark paralegals master the fundamentals and nuances of trademark practice. The course was designed by two former educators and features sessions taught by top trademark attorneys and paralegals. Learn more about Alt Legal’s Trademark Paralegal Course. Plus, check out our full collection of resources for trademark paralegals and sign up for the Trademark Administrators’ Exchange, a free email discussion group.

Patent

A patent is the grant of a property right to the inventor. In the US, patents are issued by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). With a patent, the owner has the right to exclude others from making, using, importing, offering for sale, or actually selling the invention in the US.

The USPTO issues three different types of patents: utility, design, and plant patents. Utility patents may be granted to anyone who invents or discovers a functional product, process, or machine. Design patents may be granted to anyone who invents an original and ornamental design for a functional product. Learn about the difference between design patents and trademarks in this Alt Legal guest blog article and view this Alt Legal Webinar to learn more about design patents. If a product has both a unique appearance and function, the owner may obtain both a design and a utility patent. Lastly, plant patents may be granted to anyone who invents or discovers and asexually reproduces any distinct and new plant variety.

Because patent protection provides the owner with exclusive rights, the duration of patent rights is short relative to the duration of copyright and trademark rights. A patent’s duration is limited to 20 years, and owners must publicly disclose the invention when the patent is granted. This exchange of disclosure for exclusive protection encourages continued invention and innovation, while rewarding current patent holders.

Check out our blog article: 10 Things Every Trademark Attorney Should Know About Patents

Copyright

Copyright protects original works of authorship that have been tangibly expressed in physical or digital form. Copyright encompasses the following works: literary, dramatic, musical, and artistic works, such as poetry, novels, movies, songs, computer software, and architecture. In the US, copyright protection vests upon creation and fixing the work in tangible form. Works do not need to be registered with the US Copyright Office to receive copyright protection. However, the benefit to registering a work with the US Copyright Office is that the author may collect statutory damages and attorney’s fees in a successful infringement suit.

Regardless of whether a work is registered, copyright ownership permits the author to do the following:

-

Reproduce the copyright work

-

Prepare derivative works

-

Distribute copies

-

Perform publicly

-

Display publicly

Notwithstanding these protections, the Fair Use Doctrine of the Copyright Act permits others to use a copyrighted work without the author’s permission in criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research.

Copyright protection lasts for the author’s life, plus 70 years. If the author is anonymous, pseudonymous, or created the piece as a work-for-hire, protection lasts either 95 years from the date of publication, or 120 years from the date of creation, whichever comes first. Once the term of the copyright expires, a work enters the public domain and anyone is free to use the previously-copyrighted work in any manner.

Learn about the intersection of copyright and trademark law at this Alt Legal webinar: Copyright and Copywrong: What trademark attorneys need to know about copyright.

Trademark

A trademark is a word, phrase, design, symbol, sound, or scent that identifies the source of goods or services. Trademarks protect a company’s brand and image, and they help consumers identify a company. Unlike patents and copyrights, there is no set term for the life of a trademark. Once a trademark is registered, the owner is entitled to 10 years of protection and can continue to renew the trademark every 10 years so long as the owner can prove that the mark is still being used in commerce as a source of goods and/or services.

While it is not required to register a trademark with the USPTO, common law trademark rights do exist, a registered trademark can be used alongside the ® symbol and affords the trademark owner a legal presumption of ownership nationwide and the exclusive right to use the mark in connection with the goods and/or services set forth in the application.

Types of Trademarks

The primary requirement for a valid trademark is that the mark is unique. A mark that is unique is capable of distinguishing the goods and services upon which the mark is used from other goods and services in the marketplace. Marks are categorized based on strength (strongest to weakest): fanciful, arbitrary, suggestive, descriptive, and generic.

Strongest trademarks: Fanciful and arbitrary

Fanciful and arbitrary marks are the strongest types of trademarks. Fanciful marks consist of words that have been invented for the sole purpose of functioning as a trademark, such as PEPSI and KODAK. Arbitrary marks consist of words that are commonly used but unrelated to the mark’s goods or services: they do not describe or suggest a quality about them. An example of an arbitrary mark is APPLE for computers.

Strong trademarks: Suggestive marks

Suggestive marks use words or phrases that hint at the nature of the goods or services they are associated with, requiring consumers to use their imaginations to connect the two. For example, SNO-RAKE is suggestive for a snow removal hand tool because a rake isn’t typically used with snow. A consumer would have to use their imagination to figure out what exactly the product might be doing.

Weak trademarks: Descriptive marks

Descriptive marks are weaker than suggestive marks but often the terms are confused. Descriptive marks use words or phrases that describe a quality, characteristic, feature, or purpose of a good or service. For example, BED AND BREAKFAST REGISTRY is descriptive for lodging reservation services. While the line between descriptive and suggestive marks isn’t always clear, the distinction between them is crucial because suggestive marks will default to the Principal Register, while the USPTO can refuse to register a descriptive mark on the Principal Register and instead only allow it on the Supplemental Register, unless the trademark owner has demonstrated secondary meaning or distinctiveness.

Weakest/unprotectable trademarks: Generic marks

Generic marks use common, dictionary words to describe goods and services. Trademark law prohibits the registration of generic marks. Learn how to avoid genercide by viewing this Alt Legal Connect session: When It Isn’t What It Is: Maintaining Brand Distinctiveness and Avoiding “Genericide”.

Principal v. Supplemental Register

The USPTO consists of two registers, the Principal Register and the Supplemental Register. There are a few significant advantages to registering on the Principal Register. First, marks on the Principal Register have nationwide priority over others. This means that a trademark owner can sue infringers who are using the mark anywhere in the United States. Also, registration provides trademark owners with a legal presumption that their mark is valid and that they exclusively own the mark nationwide. In the event of a lawsuit, the court will automatically view the trademark owner as the exclusive owner of a valid trademark. No further proof of validity or ownership is required. The burden will then shift to the defendant to challenge this, which is difficult, especially if the mark is highly distinct.

In addition, a mark on the Principal Register can become incontestable after it has been registered for 5 years and after the owner files a Section 15 declaration. Incontestability gives trademark owners even higher credibility in court, as registration is conclusive evidence that they exclusively own a valid trademark in the US. This means that a trademark owner’s mark will be presumed valid unless another party can prove the following:

-

The mark consists of functional matter

-

The mark owner obtained trademark registration by fraud

-

The mark is abandoned

-

The mark is used to misrepresent the source of goods or services

-

The mark violates US antitrust laws

-

The mark is generic

The Supplemental Register provides trademark owners with federal protection and benefits until they can prove that their mark has acquired distinctiveness and can register on the Principal Register. Typically, descriptive trademarks register on the Supplemental Register. By registering on the Supplemental Register, a trademark owner still gets many of the same benefits afforded with the Principal Register, such as the right to sue in federal court and the right to use the ® symbol. However, a trademark owner does not have a presumption of federal ownership when the mark is listed on the Supplemental Register. This means in order to win a lawsuit, a trademark owner has to show that the mark has “acquired distinctiveness” or that it carries a secondary meaning to consumers. For more information about the Principal and Supplemental Registers, read our article here.

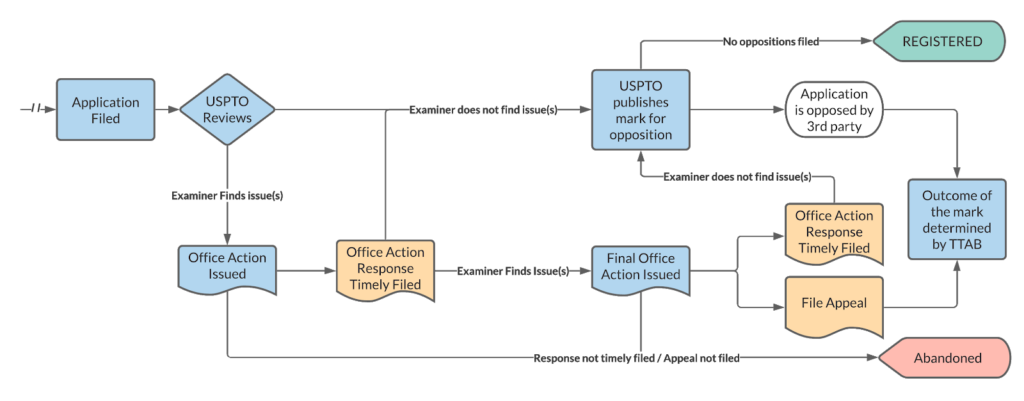

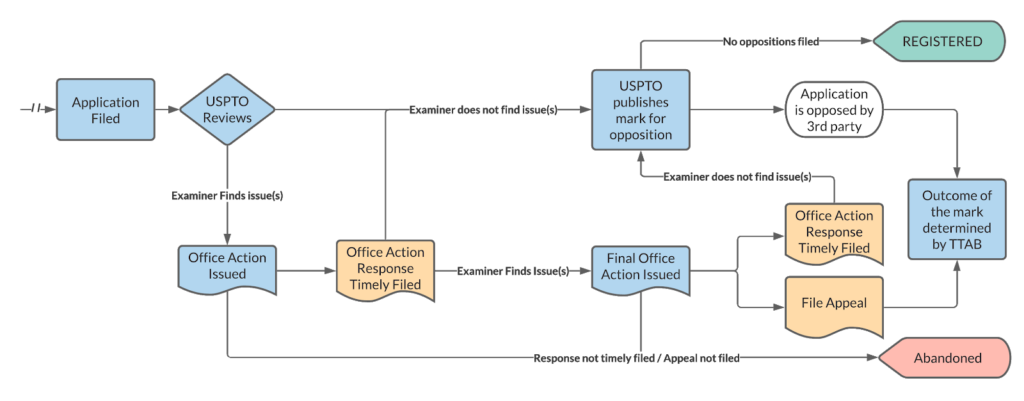

Trademark Registration Timeline

It can be a confusing and time-consuming process to register a trademark with the USPTO. During the trademark filing process, there are many legal requirements to meet and fees to pay. The USPTO sets strict deadlines to meet these requirements, and missing them can cause a trademark owner to lose rights to their application and trademark. Once a trademark owner has met all of the legal requirements for the application and the mark registers, they still need to file renewal documents and pay additional fees in order to maintain the trademark registration and keep it active.

The trademark application timeline will depend on the applicable filing basis. All trademarks, regardless of filing basis follow a similar path:

-

Application filing

-

Initial examination by Examining Attorney

-

*Occurs with many, but not all applications – Office Action(s) issued to resolve administrative and/or substantive issues with the application

-

Notice of Publication issued

-

Application published for opposition in the Official Gazette

-

Notice of Allowance issued (§1(b) application) OR Registration issued (§1(a) application)

Throughout this basic path, there are numerous opportunities for others to oppose the application. Additionally, there may be circumstances where an applicant appeals the Examining Attorney’s decision. Inter partes oppositions and ex parte appeals are heard by the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB). The TTAB is an administrative body under the USPTO that will resolve these issues and either allow an application to proceed towards registration or will prevent it from registering.

Timeline for a §1(a) Application: If a trademark owner is currently using a mark in commerce with goods/and or services, then an application should be filed as a §1(a), “in use,” application. “In use” refers to the mark being used in interstate commerce. A mark is considered “in use” for goods when (1) the mark is associated with the goods, and (2) the goods are being sold or transported in commerce. A mark is considered “in use” for services when (1) the mark is used in the sale, advertising, or rendering of services, and (2) the services are actually being rendered in commerce. One’s “use in commerce” cannot be solely for the purpose of submitting a trademark application.

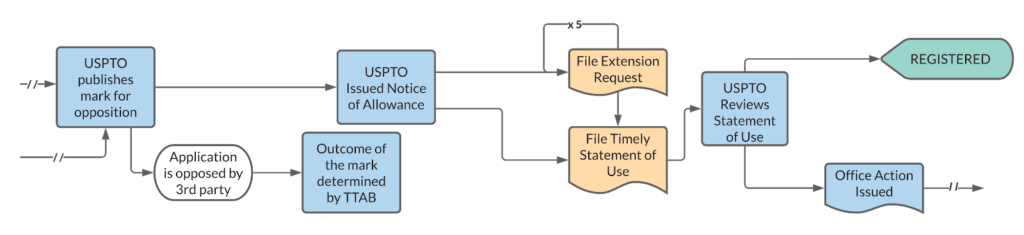

Timeline for a §1(b) Application: If a trademark owner is not yet using a mark in commerce but has a bona fide intent to use the mark in the near future, then an application should be filed as a §1(b), “intent to use,” application. An applicant who files a §1(b) application must file for registration on the Principal Register. In a §1(b) application, after the USPTO approves and publishes the mark, the USPTO issues a Notice of Allowance, permitting the applicant time to demonstrate that the mark is being used in commerce. Trademark owners may file up to five 6-month extensions of time in which to demonstrate use in commerce (by filing a Statement of Use), or else the application will lapse and become abandoned. A trademark becomes abandoned when the owner fails to take appropriate action within a specified period, causing the mark to be removed from the USPTO docket. If a §1(b) application is abandoned as a result of failing to file a Statement of Use within a 36-month period (expending all five extension opportunities), it cannot be revived and the applicant will have to file an entirely new application should they choose to pursue the mark.

Timeline for a §44(d) Application: If a trademark owner has a foreign application that was filed within the last 6 months, they may file a trademark application with the USPTO for the same mark and the same goods and/or services under §44(d). This “foreign priority basis” allows the trademark owner to take advantage of the earlier-filed application date. The earlier-filed foreign date will be applied to the US application as the effective filing date. This helps owners assert trademark rights to marks that have been filed overseas, preventing others from intercepting and filing the same or similar mark in the US. Once a trademark filed under §44(d) matures into registration in the foreign country, the application can be amended to §44(e) (see more about §44(e) in the next section).

After a §44(d) application is filed, it follows steps on a path very similar to that of a §1(a) application.

Timeline for a §44(e) Application: Similarly to a §44(d) application, if a trademark owner has a foreign trademark registration, they may file a trademark application with the USPTO for the same mark and the same goods and/or services under §44(e).

After a §44(e) application is filed, it follows steps on a path very similar to that of a §1(a) application.

Timeline for a §66(a) Application: If a trademark owner’s application is based on a filing under the Madrid Protocol, a filing treaty that ensures protection of trademarks in multiple countries, then an application should be filed under §66(a).

After Registration

After a trademark has been registered, between the 5th and 6th anniversaries of the registration, the trademark owner must file a Section 8 Declaration of Use or Excusable Nonuse. This declaration must include a verified statement that the trademark is in use in commerce, along with evidence showing that use. Failure to file this declaration will result in the cancellation of the registration. Additionally, the registrant may file a Section 15 Declaration of Incontestability, a signed statement that the owner claims incontestable rights in a trademark and continuous use of the trademark for five years. Once the Section 15 Declaration has been filed and accepted, the trademark becomes incontestable and various aspects of the registration cannot be challenged by third parties (such as the trademark’s validity).

Every 10 years, the trademark owner must again file a Section 8 Declaration of Use or Excusable Nonuse along with a Section 9 Renewal. Failing to file the combined declaration and renewal within one year following the 10th year anniversary of the registration will result in cancellation of the registration.

For trademarks filed under §66(a), owners must file a Section 71 Declaration of Use or Excusable Nonuse between the 5th and 6th anniversaries of the registration and again between the 10th and 11th anniversaries of the registration. This declaration must include a verified statement that the trademark is in use in commerce, along with evidence showing that use, or excusable nonuse. Excusable nonuse can be demonstrated by explaining special circumstances that excuse the nonuse, and that the nonuse was not due to any intention to abandon the mark. For example, if a cruise ship company was set to launch in April 2020, the owner might claim excusable nonuse because the pandemic disrupted the cruising industry. The owner must specify the reason for the nonuse and give the approximate date for when use is expected to resume. Failure to file this declaration will result in the cancellation of the registration. Finally, trademark owners must renew the international registration with the International Bureau every 10 years from the date of registration. Failing to file the combined Section 71 Declaration and renewal will result in cancellation of the registration.

Types of Office Actions and How to Respond

After filing a trademark application, the Examining Attorney will often issue an Office Action before approving the mark for publication. Office Actions are intended to resolve issues with applications so that a mark can proceed. Office Actions also prevent certain marks from registering when they do not comply with US trademark law, or they conflict with prior registrations and/or applications.

There are two categories of office actions: administrative, which address smaller issues that are usually easy to resolve, and substantive, which involve more significant legal issues as to the mark’s validity. Substantive office actions often involve claims that the proposed mark is confusingly similar to a registered mark or prior-filed application or is merely descriptive for goods or services. An attorney responds to an office action by filing an office action response. Should there be additional correspondence, filings may take the form of a request for reconsideration of the office action or an appeal to the TTAB. The TTAB handles two types of proceedings: (1) ex parte appeals for registration after the Examining Attorney has denied an application for registration; (2) inter partes oppositions, cancellations, and concurrent use or interference proceedings.

The next sections will discuss various types of administrative and substantive office actions, the laws that an examining attorney will cite, and when applicable, how to successfully respond to office actions.

§2(a) Immoral, Deceptive, or Scandalous Matter

A trademark application will be refused under §2(a) if it “[c]onsists of or comprises immoral, deceptive, or scandalous matter…” This provision encompasses many bases for refusal including curse words or other offensive language, deception relating to the geographic origin of goods (this is particularly relevant with wines or spirits), and disparaging or false connections with either living or dead persons. It is possible to overcome a §2(a) office action when there is a connection to a living or dead person but the effect is not disparaging or false. However, the owner must provide consent from the living person or the estate of a dead person.

While §2(a) refusals are often easy to spot and understand, there is some room for argument under the First Amendment to use certain terms that would ordinarily be prohibited. In a 2017 case before the US Supreme Court, members of an Asian-American rock band called The Slants argued that they had the right to register their band name as a trademark, despite the fact that the term “slants” has often been used as a disparaging, derogatory term to describe those of Asian descent. The Slants’ frontman, Simon Tam, explained that he and his bandmates wanted to reclaim the term and re-envision a term that was once a slur as a source of pride instead. The Supreme Court permitted The Slants to register their band name, holding that the disparagement clause under §2(a) violates first amendment rights.

§2(b) U.S. or Other Flag

A trademark application will be refused under §2(b) if it contains the U.S. flag, any insignia or coat of arms of the United States, any symbol of any state or municipality of the United States, or any symbol of a foreign nation. The rationale is that no one should have the exclusive right to use a flag or any other jurisdictional insignia.

§2(c) Name, Portrait, or Signature of a Living Person

A trademark application will be refused under §2(c) if it contains a name, portrait, or signature identifying a particular living individual, unless the applicant provides written consent. An application is also refused under §2(c) if it contains the name, portrait, or signature of a deceased President of the United States during the life of their widow, if any, unless the widow provides written consent. Learn more about this type of refusal and strategies to overcome and avoid it, while maintaining anonymity here.

§2(d) Likelihood of Confusion

Substantive office actions frequently cite §2(d), likelihood of confusion, as the reason for refusal. The USPTO will not register a mark that is confusingly similar to a registered mark or a pending application. The Federal Circuit set out thirteen factors (known as the “DuPont factors”) to determine whether confusion between one or more marks exists. Though the weight given to any factor may vary from case to case, key considerations include (1) the similarities of the marks as a whole considering their appearance, sound, connotation, and commercial impression, and (2) the similarities of the goods/services that are associated with the marks.

For example, consider the marks “31 US LIFE” and “US LIFE.” The applicant filing for “31 US LIFE” made a successful argument that the marks are not confusingly similar. The applicant argued that because U.S. Highway 31 is an actual highway, the mark had a different meaning an

d connotation from that of “US LIFE,” which had no association with highways and driving, and connoted the U.S. in general.

To overcome a §2(d) refusal, it is necessary to consider all of the relevant DuPont factors and argue that the applied-for mark is not confusingly similar to a registered mark. Oftentimes, a party facing a §2(d) refusal may seek a consent agreement. In a consent agreement, one party consents to another party’s registration of a similar or identical mark and explains why there is no likelihood of confusion between the marks. Strategically, it is best to first make an argument that confusion isn’t likely before seeking a consent agreement, as it will save money and time. In addition, consent agreements are only persuasive; the USPTO does not have to accept the consent agreement.

Check out our 3-part series with IP attorney M.J. Williams who describes three different scenarios and three distinct outcomes in overcoming §2(d) office actions:

Part I: Securing a Trademark Registration on the Principal Register

Part 2: Entering into a Consent Agreement with Parties Cited in Refusal

Part 3: Cancelling the Cited Mark and Seeking Registration on the Supplemental Register

§2(e)(1) Merely Descriptive

A trademark application will be refused under §2(e)(1) if it is merely descriptive of goods or services. A descriptive mark may consist of a design, a word or phrase, or a combination thereof, and serves to describe a characteristic, feature, quality, or function of a good or service. One of the reasons registration of descriptive terms is prohibited is because the USPTO wants to prevent companies from unduly harming their competitors by having a monopoly over a descriptive term.

For example, the mark “COLD AND CREAMY” is descriptive for ice cream because it describes ice cream characteristics. An example of a descriptive design mark is a cue stick and ball for a billiard parlor.

It is possible to overcome a §2(e)(1) refusal by arguing that the mark is suggestive or fanciful. Alternatively, it may be possible to argue that the mark has acquired distinctiveness under §2(f) of the Trademark Act. Read more about §2(f) here.

§2(e)(1) Deceptively Misdescriptive

A trademark application will be refused under §2(e)(1) if the mark is deceptively misdescriptive. A mark is deceptively misdescriptive if it falsely describes a characteristic, feature, quality, or function of a product or service, and if it is likely that consumers would believe in the misdescription and make a purchase based on this belief.

For example, LOVEE LAMB for seat covers, where the seat covers were not actually made from lambskin, is deceptively misdescriptive. This is because lambskin is used to make seat covers, which are more expensive and luxurious than seat covers made from other materials. Consumers are likely to believe that the LOVEE LAMB seat covers are made from lambskin and will make a purchase based on this belief. Overcoming a §2(e)(1) refusal can be accomplished by arguing that consumers are unlikely to believe in the misrepresentation.

§2(e)(2) Merely Geographically Descriptive

A trademark application will be refused under §2(e)(2) if the mark is geographically descriptive. A mark is geographically descriptive if it describes a geographic location and the goods or services for which the applicant seeks registration originates in that geographic location. In addition, it must be plausible that consumers would believe the goods or services originate from the geographic location. To support a §2(e)(2) refusal, the examining attorney must prove that the mark’s primary meaning refers to the geographical location.

For example, “VENICE” for glassware from Venice is geographically descriptive. Another example is “MANHATTAN” for cookies baked in the borough of Manhattan in New York City.

It is possible to overcome a §2(e)(2) refusal by showing that the mark’s primary significance is not the geographic location described in the mark. Alternatively, if the mark has “acquired distinctiveness,” this may be grounds for overcoming the refusal. Read more about “acquired distinctiveness” here.

§2(e)(3) Geographically Deceptively Misdescriptive

A trademark application will be refused under §2(e)(3) if the mark is geographically misdescriptive. A mark is geographically deceptively misdescriptive if: (1) the mark’s primary significance is a geographic location, (2) the goods or services for which the applicant seeks registration does not actually originate in that geographic location, (3) consumers are likely to believe in the misrepresentation, and (4) the misrepresentation is a material factor in their purchasing decisions.

The mark “BUTTER LONDON” is an example where the goods (cosmetics) were not actually associated with the city of London. The applicant successfully argued against a §2(e)(3) refusal by stating that the owner of the company was born in London and was inspired by his birth place; this showed that there was a strong association with London. It is also possible to overcome a §2(e)(3) refusal by arguing that consumers would not assume that the goods or services originate from the geographic location described in the mark.

§2(e)(4) Primarily Merely a Surname

A trademark application will be refused under §2(e)(4) if the applied-for mark is primarily merely a surname, for example, “KAHAN & WEISZ JEWELRY.” An applicant cannot register a mark that is merely a surname on the Principal Register unless that trademark has “acquired distinctiveness.” Surnames are treated this way because the USPTO recognizes that more than one person may want to use a surname in association with goods or services. Prohibiting registration of surnames absent a showing of acquired distinctiveness delays the appropriation of exclusive rights in one name.

It is possible to overcome a §2(e)(4) refusal by claiming that the mark has acquired distinctiveness. Additionally, if applicable, it can be argued that the surname is a rare name or that it has another recognized meaning. Lastly, it is possible to overcome a §2(e)(4) refusal by adding a design element or a distinctive word to a mark. Learn more about how to respond to a surname refusal.

§2(e)(5) Functional Matter

The Trademark Act allows for registration of trade dress which is the design of a product, the packaging in which a product is sold, the color of a product, or the flavor of a product. An example of trade dress is the fish shape of a GOLDFISH cracker. The shape of the cracker helps consumers identify and distinguish GOLDFISH from other products. However, the Trademark Act does not permit registration of trade dress that is merely functional. This prevents a company from having ownership over a useful product. A feature is functional as a matter of law if it is essential to the use or purpose of a product or if the feature affects the cost or quality of a product. For example, if a guitar has a particularly unique design, it could be protected as a trade dress. However, if the unique shape creates a distinct sound which is more balanced than an ordinary guitar, then the USPTO will consider the design functional and will refuse registration.

If the applied-for trade dress is merely functional, it will be refused under §2(e)(5). It is possible to overcome a §2(e)(5) refusal by providing evidence that the specific product feature doesn’t provide any useful advantages but is one of many equally feasible, efficient, and competitive designs. Evidence may include showing how a product feature has been promoted to help consumers identify the brand. Learn more about the difference between trade dress and design patents.

§2(f) Acquired Distinctiveness

As discussed in prior sections, an office action refusal can be overcome if it can be shown that a mark has “acquired distinctiveness” pursuant to §2(f). Unlike the other sections previously discussed that are grounds for refusal, §2(f) permits non-distinctive marks (aka, descriptive marks) that have acquired distinctiveness to register on the Principal Register. If a mark has acquired distinctiveness, this means that the mark has significance to consumers and that they identify the mark as a source indicator of goods or services and not by its dictionary meaning.

Acquired distinctiveness can be demonstrated using evidence to demonstrate the following:

-

Prior Registrations: Where a mark owner has an existing trademark registration for goods/services that are sufficiently similar to the goods/services in the pending trademark application. AND/OR

-

Five Years’ Use: Where a mark owner has exclusively and continuously used a mark in commerce for five years. AND

-

Other Evidence: Other types of evidence include long-term use of the mark, large scale expenditures in promoting and advertising goods/services with the mark, and declarations from consumers that they recognize the mark as a source indicator.

For more information on overcoming refusals and proving acquired distinctiveness, check out our article here.

The Controlled Substances Act

A trademark application that lists under its goods and/or services any products or services that fall under the jurisdiction of the Controlled Substances Act will be refused registration. Trademark law prohibits registration of marks that reference goods or services that a company cannot lawfully sell across state lines. Under the Controlled Substances Act, it is unlawful to manufacture, distribute, dispense, possess or sell any controlled substance. Regardless of state law, cannabis remains a controlled substance under federal law, and therefore registration of a mark for cannabis is prohibited. For more about registering trademarks related to cannabis, check out this article, this webinar, and the recorded content from Alt Legal Connect 2020.

Failure to Function: Overview

An applied-for mark will be refused when it fails to function as a trademark, which is to say that it does not identify the source of the goods or services. Often a failure to function refusal is based on a bad specimen because the specimen does not show the mark in use in commerce. In this case, the applicant may be able to overcome a failure-to-function refusal by submitting a new specimen showing the mark used on storefronts, in-store displays, websites, print and digital advertising, and actual products and merchandise. For more about specimen requirements, check out this article.

There are many other reasons why a mark may fail to function as a trademark. Check out this article about the various reasons why a mark may be cited for failure to function. Additionally, this article provides a complete overview of failure to function for merely informational matter, widely used messages, and religious text. Also, it is important to note that the USPTO is issuing failure to function refusals quite liberally, as discussed in this article.

The following sections discuss various reasons why marks may be refused for failure to function.

Failure to Function: Hashtags

Marks that contain hashtags rarely qualify for registration. Hashtags are used to identify or search for a word on social media sites. When an applied-for mark contains a hashtag symbol, it must be shown that the entire mark is used in commerce, not just as a hashtag for online social media. Consider the example below, where the applicant overcame a failure to function refusal by submitting a new specimen.

The first image does not show the mark “#BEATTHECRAVING” in use in commerce. The second image shows that the mark functions like a trademark, because it is used with the restaurant services. For more information about social media trademarks, including those with hashtags, check out this webinar.

Failure to Function: Ornamental Use

Ornamental use means that the applied-for mark contains designs, symbols, words, or phrases that do not identify a source. For example, the phrase “HAVE A NICE DAY” printed across the front of a t-shirt is not a trademark because it does not identify the source of the goods; it is merely an ornamental phrase. The phrase does not act as a trademark because it does not indicate the business or entity that created the t-shirt.

It is possible to overcome an ornamental refusal by showing how the mark at issue clearly signifies an association with the mark owner’s business. One way to do this is by submitting a new specimen that shows the mark on a label or tag. The label or tag should be attached to the clothing goods, showing that the mark functions like a trademark. Learn more about ornamental refusals.

Failure to Function: Domain Names

It can be very challenging to register a trademark containing a generic top level domain (TLD), such as “.com,” “.edu,” and “.org”, as TLDs cannot act as a source identifier, and generally, cannot constitute a part of a registered mark unless they are part of the company name. Notably, the US Supreme Court took up this issue in 2020 and decided to allow Booking.com to register a trademark for BOOKING.COM. For more about the Booking.com case, watch the recording of this webinar. To use a TLD in a trademark, it must be shown that consumers perceive the mark as something more than an internet address.

After the Booking.com case, the USPTO issued an Examination Guide to address the procedures involved in examining trademark applications for generic terms combined with TLDs. The guide explains how a generic term will be assessed and outlines the types of evidence that will support consumer perception as a source identifier. Also, check out this article about filing generic.com trademark applications after the Booking.com case.

Failure to Function: Matter Used Solely as a Trade Name

An applied-for mark will be refused if it is solely used as a trade name; the Trademark Act does not provide for registration of trade names. A trade name is another term for “doing business as” (DBA) names. Trade names are often used by sole proprietors in conducting business in order to present a more professional image. This is different from a trademark, which is a word, phrase, design, or symbol that associates goods or services with a business. Trademarks, by definition, are usually more distinctive than trade names.

A company may use its trade name in its trademark. For example, The Coca-Cola Company is the business entity or trade name that sells the COCA-COLA brand beverage. However, if the trade name does not also function like a trademark, the examining attorney can refuse to register the mark on the grounds that it is merely a trade name. The examining attorney will consider the mark’s probable impact on consumers and how the mark is presented with goods and services when making this determination.

To overcome a claim that a mark is merely a trade name, it will be necessary to submit specimens showing how the mark functions like a trademark. The mark should be prominently displayed in use in commerce with goods and/or services. In addition, it must be argued that consumers use the mark to identify the owner’s brand and to distinguish it from others.

Failure to Function: Generic Marks

An applied-for mark will be refused if it is a generic term. A mark is generic if it uses words that the public understands as the common term for goods or services. For example, the term “PILLOWS” cannot achieve trademark protection for a company that produces pillows. If an examining attorney believes that a mark is generic, the proper basis for the refusal is §2(e)(1), that the mark is merely descriptive. In the case of applied-for marks that are apparently generic, the examining attorney will include a statement in the office action that the mark appears to be generic for the goods or services listed in the application.

It can be difficult, and almost impossible to overcome a refusal for a mark that is considered generic. It must be shown that the mark as a whole is not generic for goods or services. For example, the mark “SOCIETY FOR REPRODUCTIVE MEDICINE” for a reproductive medicine association was considered descriptive, not generic because the examining attorney failed to provide evidence that the public would understand the mark as a whole to be the common term for the association. While descriptive trademarks are inherently weaker than fanciful, arbitrary, or suggestive marks, they can still be placed on the Supplemental Register, unlike generic trademarks, which cannot be registered on either the Principal or Supplemental Registers.

Failure to Function: Prohibition on Plant Varietal

An applied-for mark will be refused if it is a varietal name which is used in a plant patent to identify the plant variety. A varietal name cannot function as a trademark if it is used in connection with its respective plant variety; otherwise it will be considered generic.

For example, a trademark applicant attempted to register the mark “SANSIBAR” for plant seeds. “Sansibar” is the varietal name for various plants, including corn, rapeseed, beets, rhododendron, and ryegrass. The applicant overcame a failure to function refusal by amending the identification of goods in the trademark application to state: “live plants and natural flowers thereof, excluding corn, rapeseed, beet, rhododendron, and ryegrass.” As a result, the mark was no longer considered generic.

Including a Disclaimer

When submitting a trademark application, the applicant may include a disclaimer, indicating that the mark contains a descriptive or generic term over which the applicant claims no exclusive rights. A disclaimer permits registration of a mark that is registrable as a whole, but contains matter that would not be registrable standing alone. For example, in “STARBUCKS COFFEE,” the word “coffee” was disclaimed. Starbucks has the exclusive right to use the mark as a whole, not the word “coffee” standing alone.

If the applicant does not include a disclaimer for a descriptive or generic term as part of the trademark application, the examining attorney may ask the applicant to submit a disclaimer.

The following format is preferred when disclaiming matter in a mark:

“No claim is made to the exclusive right to use ‘_____’ apart from the mark as shown.”

Check out this video about how to search for disclaimers using USPTO Trademark Search.

Failure to Identify Goods and Services

The examining attorney may require the applicant to amend the application if the goods or services in the application are not identified correctly. To prevent this, it is important to identify the goods/services in the application in a definite, clear, accurate, and concise manner. For products or services that do not have common names, it is best to use clear and succinct language to describe or explain them. The average person should be able to understand the identification.

For example, if an applicant described a mark’s goods as “blankets,” that would not be sufficient to identify the type of blanket on which the mark is used. This is because “Blankets” could mean fire blankets (Class 9), electric blankets for household purposes (Class 11), horse blankets (Class 18), or bed blankets (Class 24). Applicants must specifically identify the type of goods and services so that the application is filed in the correct class. Failure to do so will result in an office action where the examiner will request clarification of the specific goods and services with which the mark is used.

Check out this video about how to search for goods and services using USPTO Trademark Search.

Trademark Application Tips & Strategies

Choosing a Strong Mark

When a client hasn’t yet selected a trademark, attorneys should advise them to choose a mark that will be easy to protect, like a fanciful or arbitrary mark. Many businesses understandably want to choose descriptive marks because they are easiest to develop and to market, as consumers understand right away what the product is based on the trademark. However, a weak trademark will not afford much protection, and it could take years for the mark to register on the Principal Register.

Once a client has developed a mark, the next step is to conduct different levels of searches to assess the mark’s availability. The first type of search is a simple knock-out search using various search engines, databases, and the USPTO trademark database, to ensure that the mark is available. Check out our video tutorials for conducting searches using USPTO Trademark Search. Once this initial screening search has been conducted, it is recommended that additional, more thorough searches be conducted using a trademark search company. The company will provide an extremely thorough search of paid and unpaid databases, compiling a report of any potentially similar and/or confusingly similar marks. The attorney will then review the results of the report (which is often several hundred pages long), extracting the important information and reporting the findings to the client by writing a trademark search opinion letter. It is critical that the attorney properly assess risk and identify marks that may later be raised by the examining attorney or whose owners may claim infringement. It is possible that after reviewing the results of the trademark search, the attorney may deliver a negative opinion and advise the client not to proceed with filing a trademark application for the chosen mark.

Register a Word Mark First

It is common practice to begin building a client’s trademark portfolio by first filing an application for a word mark. Word marks offer the broadest scope of protection because a word mark protects the word or phrase regardless of how it is displayed. For example, registering a word mark for “ALT LEGAL” protects the mark in any font, size, or color. A trademark owner who registers a word mark has the option of modifying the mark to any color or font later on.

However, if a client’s mark contains words and a unique design, then it makes sense to file two separate applications: one for the word mark and a second for the combined word and design mark. While it is more expensive to file two separate applications at the onset, this strategy will be most effective in securing a client’s trademark rights.

Delay Disclosure of the Trademark

When anyone files a trademark application with the USPTO, it becomes public record. Anyone tracking new filings will immediately become aware that a person or entity is seeking protection over a particular term in connection with specific goods and/or services. For persons or entities hoping to avoid disclosure of their future business plans (for a short time) can strategically file a trademark application in a foreign country that does not have a publicly searchable database. Within six months of filing abroad, US trademark applicants can then file an application with the USPTO pursuant to §44(d). As previously discussed, this provision allows an applicant to file a US trademark application based upon the earlier-filed foreign application. §44(d) allows applicants to apply the foreign filing date to the US application, conferring early trademark rights to the applicant without having to publicly disclose the mark on an earlier date. This strategy is particularly helpful when an entity wants to prevent competitors from finding out about their trademark applications and business developments. §44(d) gives companies almost six months of secrecy without losing any of the rights they would have had if they had filed in the US first. Read this article and this article for more information about this strategy.

Be Careful of Genericide

A mark can quickly devolve from fanciful and arbitrary to generic if not properly protected. For example, “escalator” and “aspirin” are both generic terms that were once registered trademarks. The owners of these marks failed to properly protect the marks and to reinforce their brand’s connection with the product. In addition, they failed to sue other companies for using their marks. This resulted in “genericide,” when a protected mark becomes generic for its goods or services over time. In order to avoid trademark genericide, trademark owners (and their attorneys) must police the marks in their portfolio marks and enforce their trademark rights. For more about genericide, check out Josh Jarvis and Tish Berard’s recorded content from Alt Legal Connect 2020.

Letters of Protest

Anyone who thinks there is a good reason why another mark should not register can write a letter of protest. Common grounds for writing a letter of protest include: the mark is confusingly similar to a registered mark, the mark falsely suggests a connection with someone else’s brand, or the mark is descriptive. Attorneys must carefully monitor applied-for marks and the Official Gazette for published marks in order to determine whether a mark in a newly-filed application conflicts with marks on their portfolios. The attorney should submit a letter of protest as soon as possible after an application has been filed or within 30 days of the mark’s publication in the Official Gazette. This can be a difficult, manual, and cumbersome process which is why Alt Legal developed its novel §2(d) Trademark Watch. Any time an examining attorney finds that an applied-for mark is confusingly similar to any of the marks on your docket, you will receive an email notification, allowing you to take swift action by way of a Letter of Protest or other means. To learn more about Alt Legal’s §2(d) Trademark Watch, click here. For a step-by-step plan for handling notifications from Alt Legal’s §2(d) Trademark Watch so that you can effectively respond to potential infringement, click here. Also, check out our webinar about how make best use of Alt Legal’s §2(d) Trademark Watch: 2(D)iscover Potential Infringement: Using Alt Legal’s §2(d) Watch Effectively.

U.S. Counsel Requirement

Attorneys who sign off on an office action response become counsel of the entire application. However, it is possible to withdraw as attorney of record by filling out the Attorney Withdrawal Form on the USPTO website.

As of August 2019, U.S. Counsel is required for all foreign domiciled and foreign registered applications. This requirement is meant to increase USPTO customer compliance with U.S. trademark law, improve the accuracy of trademark submissions, and safeguard the integrity of the U.S. trademark register.

Conclusion

While there are many steps and possible hurdles to overcome after filing a trademark application, the process need not to be intimidating! By adhering to all deadlines and satisfactorily responding to any office actions or requests for additional information from the USPTO, marks can be successfully registered. Once a mark has registered, it is essential to maintain the registration by filing appropriate declarations and renewals. Additionally, attorneys must monitor the registered mark to protect it against infringement and/or genericide.

If you have questions or need further information about any of the topics discussed in this eBook, or if you would like to set up docketing for your new or existing IP practice, please visit altlegal.com or schedule a call to learn more.