Failure to Function – Informational Matters, Widely Used Messages, and Religious Text

Jeffrey Turben | May 26, 2021

Introduction

If an applied-for mark mostly or exclusively conveys information about a product or service, the mark is considered merely informational matter and will be refused based on failure to function. Like the determination for ornamentality, whether an applied-for mark is merely informational is determined based on the evidentiary record and the relevant public’s perception of the mark. Specifically, the standard states, “The critical inquiry in determining whether a designation functions as a mark is how the designation would be perceived by the relevant public. To make this determination we look to the specimens and other evidence of record showing how the designation is actually used in the marketplace.” In re Eagle Crest Inc., 96 USPQ2d 1227, 1229 (TTAB 2010)

There are three sub-categories of subject matter that have been deemed to function as mostly informational matter:

(1) General information about the good or service.

(2) A phrase or message that is common with respect to advertising practices in the industry or everyday life.

(3) “A direct quotation, passage, or citation from a religious text used to communicate affiliation with, support for, or endorsement of, the ideals conveyed by the religious text.”

U.S.P.T.O., Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure § 1202.04 (Oct. 2018).

While it is possible to overcome a merely informational refusal with the proper arguments, it is important to note that when faced with a merely informational refusal, an applicant cannot claim acquired distinctiveness under Section 2(f) (15 U.S.C. § 1052(f)), nor can the applicant seek to register the mark on the Supplemental Register, as it does not meet the statutory definition of a trademark.

Marks Conveying General Information

Marks that consist of merely informational matter, including laudatory remarks or puffery, must be refused on the basis of their failure to function as trademarks. U.S.P.T.O., Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure § 1202.04(a) (Oct. 2018). For example, it is unlikely that a consumer would consider a mark consisting of the phrase “THE BEST BEER IN AMERICA” as acting as a source-indicator for a particular manufacturer of beer. See generally In re Boston Beer Company LP, 198 F.3d 1370 (Fed. Cir. 1999) (rejecting a claim of acquired distinctiveness under §2(f), the court held that the mark “THE BEST BEER IN AMERICA” was incapable of acting as a source-identifier due to it being a common laudatory phrase used in advertising).

Since consumer perception is key to whether a mark is a source indicator, examiners will look at the trade practices of the applicant’s industry as well as encyclopedias and dictionaries to understand the meaning of a mark’s words or imagery. The examiner will also look at supporting evidence such as social media and the applicant’s promotional materials to determine whether the applied-for mark is used as a trademark. Specifically, examiners will compare applied-for marks to subject matter that is undisputedly informational to understand how consumers would perceive the positioning of the applied-for mark in relation to the product or service at issue.

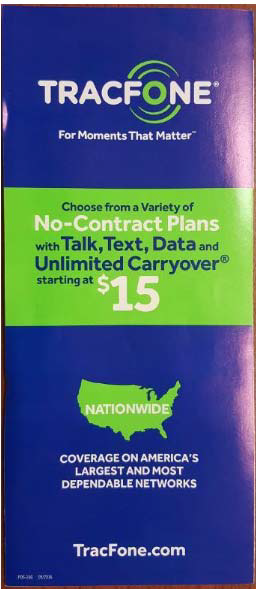

For example, in In re TracFone Wireless, Inc., 2019 U.S.P.Q.2d 222983 (TTAB 2019), the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) refused the mark UNLIMITED CARRYOVER as merely informational.

In determining that the mark was merely informational, the Board found it significant that on the specimen of use, the mark was positioned among other service information, including service pricing ($15/ month) and specific service offerings (no-contract talk, text, and data services). In addition, the applicant set forth no evidence that the public perceives the applied-for-mark as a source indicator. The examiner also conducted a textual analysis, citing dictionary definitions of “UNLIMITED” and “CARRYOVER,” and ultimately claimed that the applied-for mark was simply conveying the particulars about the applicant’s services.

Therefore, a mark is likely to be found merely informational and refused registration when:

-

The mark is situated among informational material;

-

There is no evidence to suggest that consumers would view the mark as something other than informational subject matter; and

The mark consists of wording that is descriptive of applicant’s products or services.

Marks Containing Widely Used Messages

Widely used messages are refused registration because they convey ordinary or familiar concepts or sentiments. Widely used messages include commonly used slogans, terms, and phrases as well as social, political, religious, or similar informational messages that are in common use or are otherwise generally understood. U.S.P.T.O., Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure § 1202.04(b) (Oct. 2018). The more ubiquitous a term, phrase or expression is, either in the relevant industry or in everyday life, the less likely consumers are to perceive the mark as a trademark. In re Eagle Crest, Inc., 96 USPQ2d 1227, 1229-30 (TTAB 2010).

Products adorned with widely used messages are often purchased for the sentiments they convey, not because the mark identifies a particular entity that the consumer perceives as adding value. U.S.P.T.O., Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure § 1202.04(b) (Oct. 2018). For example, a mark consisting of text that reads “I ♥️ DC” on an article of clothing is unlikely to be associated with any one entity. Instead, consumers understand the mark to be a statement of enthusiasm regarding the District of Columbia. See D.C. One Wholesaler, Inc. v. Chien, 120 USPQ2d 1710, 1716 (TTAB 2016) (finding that the mark “I ♥️ DC” would evoke an affectionate sentiment in the minds of the consumer, the TTAB concluded that the mark necessarily did not function as a trademark).

In order to determine if a mark conveys a widely used message, examiners will look at a wide variety of evidence including social media, news, and any other relevant matter to decide whether the mark is ubiquitous. U.S.P.T.O., Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure § 1202.04(b) (Oct. 2018). In addition, the size, position, and prominence of the mark, relative to the good, may also be considered. Id. Furthermore, examiners will look at whether the applicant or third-parties use the mark as adornment, suggesting that the applied-for mark is not a source indicator. In re Hulting, 107 USPQ2d 1175, 1179 (TTAB 2013).

By way of example, in In re Deporter, 129 USPQ2d 1298 (TTAB 2019), the TTAB found that an applied-for mark consisting of the text #MAGICNUMBER108 was merely a common expression, despite the fact that the mark was first used by the applicant. The mark refers to the Chicago Cubs’ 2016 World Series win, after a 108 year “drought” of not winning a World Series. The applicant, Grant Deporter, CEO of Harry Caray’s Restaurant Group, had co-authored a book, Hoodoo: Unraveling the 100 Year Mystery of the Chicago Cubs, in which he identified a list of appearances of the number 108 in reference to baseball (108 stitches on a baseball) and the Chicago Cubs (the distance between foul poles at Wrigley Field is 108 meters.) The applicant explained that the significance of the number 108 could be used to predict that the Chicago Cubs would win the 2016 World Series, 108 years after its last win in 1908.

The examiner presented evidence that there were numerous appearances of the applied-for mark in third parties’ social media posts, including posts on Twitter and Instagram, suggesting that consumers would only perceive the mark as conveying a common sentiment, namely feelings of surprise and jubilation regarding the Cubs’ big win. Additionally, the specimen was deficient and did not properly show the mark in connection with the sale of any product or service. Instead, the specimen merely showed the applied-for mark in news articles discussing applicant’s prediction that the Cubs would win the World Series.

On appeal, the TTAB upheld the examiner’s refusal, finding that the applied-for mark was used in a non-trademark manner to refer to the Cubs’ World Series win and that consumers familiar with the mark usage were unlikely to consider the mark as a source indicator for the applicant’s goods. Rather, due to the widespread use of the mark on social media, the mark merely conveys an informational reference to the Cub’s appearance at the 2016 World Series, and the mark fails to function as a trademark. The mark was refused registration and ultimately abandoned.

Religious Text

Religious texts, or derivatives thereof, do not function as trademarks and are refused registration because their primary function and perception among consumers is that of an expression of agreement with or affirmation of the text. U.S.P.T.O., Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure § 1202.04(c) (Oct. 2018). Even if a mark contains registrable elements, the religious text portions of the mark must be disclaimed. Id. In making a determination, the examiner will consider any evidence showing that the religious matter is typically used by marketplace pa

rticipants to proclaim support for, affiliation or affinity with, or endorsement of a religion. Id. Finally, marks containing actual quotes or translations of religious text or portions thereof should be refused under TMEP §1202.04(c). For example, if an applied-for mark merely expresses religious sentiment but is not a direct quote or translation of a religious text, then it may not be rejected under §1202.04(c) (Religious Texts), but it may be rejected under §1202.04(b) (Widely Used Messages).

For instance, a mark consisting of the text KEEP CALM AND FOLLOW JESUS would likely be rejected under §1202.04(c), or, in the alternative, under §1202.04(b). With respect to §1202.04(c), the primary function of the statement is likely to be perceived by consumers as expressing affirmation towards or agreement with the principles or ideals embodied in Christianity, rather than a source indicator. In particular, the “FOLLOW JESUS” portion is likely to be a direct quote, translation, or interpretation of actual religious text. Additionally, the “KEEP CALM” portion of the mark would likely be held to be a commonplace expression, given the ubiquity and everyday usage of the phrase “KEEP CALM AND CARRY ON” and other variations thereof. It is unlikely that KEEP CALM AND FOLLOW JESUS would register given that certain designations are inherently incapable of functioning as trademarks to identify and distinguish the source of goods. American Velcro, Inc. v. Charles Mayer Studios, Inc., 177 USPQ 149, 154 (TTAB 1973).

Overcoming a Merely Informational Refusal: Play on Words

The primary factor in determining whether an applied-for mark constitutes merely informational matter is consumer perception. It is possible to overcome an initial refusal that the mark consists of merely informational matter by demonstrating that consumers will perceive the mark as a source indicator.

For example, the mark UCK OFF was initially refused on the basis that it was merely informational and, specifically, was a commonplace term or expression. Office Action Regarding Trademark Application Serial Number 88593362 (Nov. 21, 2019). Producing evidence from eBay, Amazon.com and Etsy.com, among other eCommerce platforms, the examiner asserted that consumers would perceive the mark as a derivative of the commonplace expression “FUCK OFF.” The examiner presented an example of “FUCK OFF” being used in commerce, as well as conveying informational subject matter, namely the sentiment or thought of wanting to be left alone. Id.

In response, the applicant argued that while the term “FUCK OFF” is commonly used, the term “UCK OFF” is not widely used, noting that there was only one seller marketing products that featured the term “UCK OFF.” See Response to Office Action Regarding Trademark Application Serial Number 88593362 (May 26, 2020). Also, the applicant submitted eight pages of Google search results that did not feature a single example of the term “UCK OFF” being used in commerce. In terms of the phrase’s meaning, the applicant argued that UCK OFF was a play on words. The mark was to be used in connection with cleaning supplies and that “UCK” refers to grime, dirt, and other debris. As a result, consumers would not perceive the mark UCK OFF as the commonplace term or expression”FUCK OFF”. The applicant also noted that because the mark is a play on words and is not conveying general information about what the product does (merely general informational matter), it is registrable. In support of this argument, the applicant attached examples of other marks that consisted of plays on words, such as the mark HIT HAPPENS for legal services, which is similar to the common expression “SHIT HAPPENS.”

The examiner accepted the applicant’s arguments and allowed the application to proceed to publication. Ultimately, the application matured into registration.

Overcoming a Merely Informational Refusal: Providing Context for Common Expressions

Alleging and producing evidence suggesting that consumers would perceive an applied-for mark as something more than general information or a commonplace expression should help an applicant overcome a merely informational refusal. Another way for an applicant to overcome a merely informational refusal is to demonstrate that the mark, while a common expression, is being used in connection with goods or services that are unrelated to the context in which the phrase is typically used.

The mark GET’EM OVER GET’EM IN (for educational services, using sports to teach life lessons to athletes) was initially refused on the basis that it was merely an informational slogan. Office Action Regarding Trademark Application Serial Number 88328669 (May 15, 2019). Attaching evidence from news media and baseball-related websites, the examiner argued that the applied-for mark was a common and widespread expression of encouragement and a “famous adage from baseball.” The examiner asserted that consumers would perceive the applied-for mark as merely informational matter, namely, a commonly-used slogan. The examiner cited In re Volvo Cars of N. Am., Inc., 46 USPQ2d 1455 (TTAB 1998), where the mark DRIVE SAFELY (for automobiles and automobile parts) was rejected as merely an informational slogan that consumers perceive as a commonplace expression.

In response, the applicant argued that the examiner should not have applied a de facto rule regarding common phrases, and instead should have looked to whether the way in which the phrase is used, with respect to applicant’s services, is unique enough to warrant trademark registration. Response to Office Action Regarding Trademark Application Serial Number 88328669 2 (Nov. 15, 2019) (citing Fisons Horticulture, Inc. v. Vigoro Indus., Inc., 30 F.3d 466 (3d Cir. 1994)). Such a suggestion carries weight because whether a mark functions as a trademark is a determination that must be made on a case-by-case basis. U.S.P.T.O., Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure § 1202.04(d) (Oct. 2018).

The applicant argued that although the applied-for mark did consist of a common phrase with respect

to baseball, the phrase was not common in the context of educational services. Additionally, the applicant asserted that the facts in In re Volvo were distinct from the application at hand. While Volvo was attempting to register a common phrase related to driving for automobiles and automobile parts, here the applicant was attempting to register a term typically associated with baseball but in this case used for educational services. The applicant argued that the applied-for mark in the context in which it was being used was unique enough to warrant a registration.

The applicant’s arguments were persuasive: the examiner allowed the application to proceed, and it was successfully registered.

Conclusion

There are certainly many scenarios where a mark simply cannot be registered because it consists of merely informational matter. But there are also many scenarios in which the refusal can be overcome with proper explanation and context. A mark may receive an initial refusal because the examiner simply doesn’t understand the full context of the way in which the mark is used and the way in which consumers perceive the mark. It is important to set forth arguments and evidence in a way that addresses the examiner’s reasons for refusal and demonstrates the registrability of the mark. Often providing more context or looking for incongruities between the applicant’s mark and the cited precedent can help you overcome a merely informational refusal.