Memes and IP Protection

Margo Cruz | June 30, 2020

Viral Internet memes have had a massive impact on popular culture, but has there been an impact on intellectual property practices? Memes can hold great brand power, and some meme-makers have successfully registered trademarks and copyrights, while others have missed their chance. Memes are still disputed territory in the intellectual property world.

Lizzo

One trademark currently in dispute is the viral tweet/meme/lyric “100% THAT BITCH.” The singer Lizzo applied to trademark the phrase after her hit song “Truth Hurts” included the line.

The USPTO only recently began allowing trademarks that include words like “bitch” as a result of the 2019 decision in Iancu v. Brunetti. Such marks previously would not have been allowed because of the Lanham Act’s Section 2(a) prohibition on “scandalous” and “immoral” trademarks. The Supreme Court held in Brunetti that the this prohibition violated the First Amendment because it resulted in viewpoint discrimination—the government was approving marks that expressed “accepted” views while denying marks that expressed other views on the same topics.

Lizzo’s ability to register the trademark, however, appears difficult on other grounds. Lizzo admitted in a tweet that the line from her song was inspired by a circulating Twitter/Instagram meme: “I just took a DNA test and found out I’m 100% that bitch.” Mina Lioness, a British singer, was the first to tweet this line in 2017. The back and forth between Mina Lioness and Lizzo had been documented in multiple articles, but it took a long time for Lizzo and her team to acknowledge Mina Lioness’s contribution. However, she is now finally credited as a writer on “Truth Hurts.”

Despite the admission, Lizzo’s team filed a section 1(b) intended-use application in June 2019. So far, Lizzo is the only applicant to attempt to trademark the phrase, and her team has sent four separate applications each with different goods and services categories, which is probably a strategy meant to facilitate the fastest registration.

The USPTO’s first office action response stated that the proposed mark fails to function as a trademark or source identifier of the goods and is simply a “commonplace term, message, or expression widely used by a variety of sources that merely conveys an ordinary, familiar, well-recognized concept” (TMEP 1202). There was also a letter of protest submitted by someone named Rosemary Jackson, similarly alleging that the applied-for mark failed to function as a source identifier.

In response, Lizzo’s legal team argued that other “100% That Bitch” goods were infringing upon Lizzo’s rights and taking advantage of her “tremendous goodwill and notoriety” to sell “knockoff goods.” The response noted that e-commerce websites like Etsy included “Lizzo” and “Truth Hurts” in their keywords which usually increase the visibility of the goods for sale. Lizzo’s team used these tags as evidence that others were profiting from Lizzo’s notoriety.

Unfortunately for Lizzo, on June 10, 2020 the USPTO issued a second office action questioning Lizzo’s intellectual property rights to the phrase and maintaining the failure to function issue stated above. This may be the end of the road for this trademark application, and it may show the effectiveness of a letter of protest (standards available in TMEP 1715.02(a)). This may also be an example of the difficulty of trademarking a meme that one has not personally created, especially after it has gained popularity. As one can see from other examples below, trademarking memes of one’s own creation is not so difficult, but there are some caveats.

Damn Daniel

The Damn Daniel meme presents an interesting study of valid trademark application specimens. The creators of the now famous line, “Damn Daniel, back at it again with the white vans,” took their meme much further than most: the duo formed a corporation, Damn Daniel LLC, and successfully trademarked their meme twice: DAMN DANIEL and DAMN DANIEL BACK AT IT AGAIN.

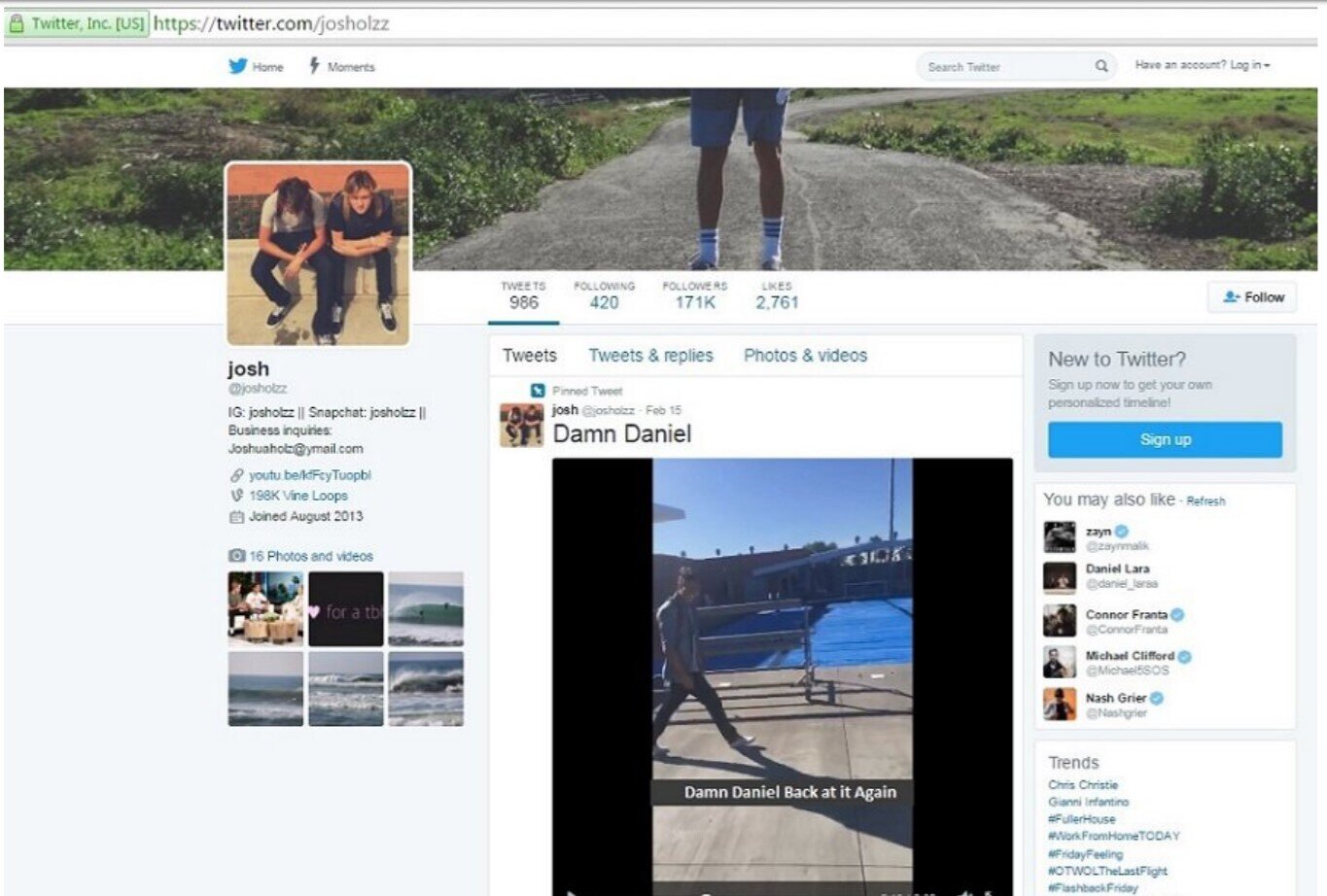

The specimen for “DAMN DANIEL BACK AT IT AGAIN,” simply a screenshot of Josh Holz’s Twitter page, is interesting because of its corresponding office action:

This specimen elicited an office action for “failure to show the mark in use in commerce.” More specifically, “the specimen fails to make reference to any services, even the broadly stated ‘services having the basic aim of the entertainment, amusement or recreation of people’” (See TMEP 904.03).

The office action went on to say that the specimen did not show use on an advertisement or in connection with the applied-for goods, and “The submitted specimen is not such that the examining attorney may reasonably assume that consumers will make an association between the mark and the recited service.” This response suggests that social media pages without explicit advertisements using the applied-for mark may not be considered use in commerce for the purpose of trademark registration. Of course, this is just one example and one specimen.

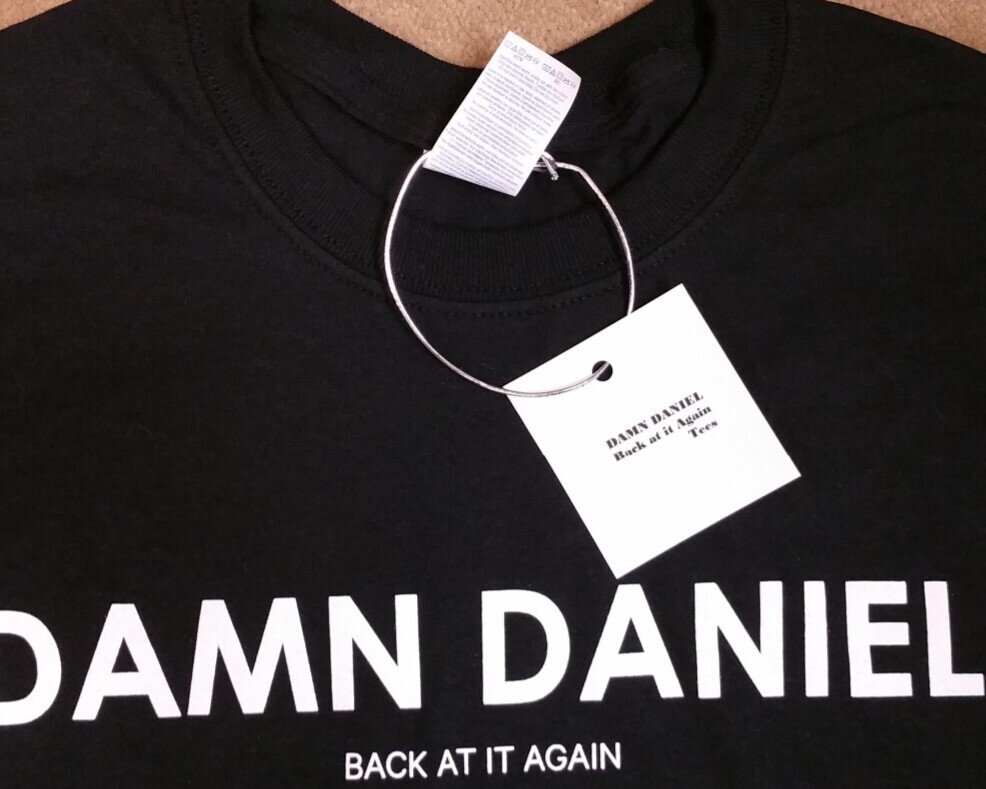

To resolve this office action, Damn Daniel LLC submitted a more standard specimen: the words “Damn Daniel Back At It Again” on the sales tag of a t-shirt. In the specimen below, note it is not the words on the chest of the t-shirt that show use in commerce—those are merely ornamental—but rather it is the use of the applied-for mark on the tag that acts as a source indicator.

Grumpy Cat

Grumpy Cat first gained popularity in 2012. The owners also formed a corporation, Grumpy Cat Limited, and filed for several trademarks of “GRUMPY CAT” in 2013. The cat owners’ quick response to their popularity may have been the reason for success in trademarking. Grumpy Cat even did a collaboration with Friskies, and applied for a trademark using that image as a specimen. The owners also registered “GRUMPY CAT” for plush toys, coffee and tea, and other miscellaneous merchandise.

As a case study for meme trademarks, Grumpy Cat’s biggest lesson may be to respond to popularity quickly and start using your meme effectively in commerce as a source identifier, which likely helps with trademark applications down the road.

Success Kid

Another example of a meme creator successfully benefiting from the meme, and enforcing her intellectual property rights is “Success Kid.” In this case, the creator used copyright to protect the meme.

After the picture of a triumphant-looking baby holding up a fistful of sand became popular on many websites, the boy’s mother registered the copyright in 2012. Laney Griner licensed the photo to several brands for advertising and has been diligent in enforcing her rights where the photo has been used for commercial purposes. When Iowa Congressman Steve King used the meme image without her permission in a fundraising campaign, her attorneys promptly sent a letter demanding removal of the image and payment of any funds gained as a result of the ad’s use. Luckily, Griner has a significant enough presence on the internet that social media users have usually alerted her to commercial uses of the image.

OK Boomer

OK Boomer has seen a flurry of applications since its popularity around 2018. Notably, Fox Media has applied to trademark the phrase for a potential reality TV show. Another applicant sought to trademark “OK BOOMER,” for board games and trivia games, a 44(d) application from Canada. Another application is “OKBOOMERDAD,” a 1(b) application for entertainment content. While the initial goods and services identification was too indefinite, the wording, “an on-going series featuring comedy provided through webcasts on the Internet,” was sufficient. OKBOOMERDAD has now received a notice of allowance, so hopefully we will see a specimen example soon. Check out @okboomerdad on TikTok.

Conclusion

As it stands, to become protected intellectual property, memes must conform to long-established regulations. As memes continue to enter mainstream culture, the effect on the intellectual property world will become clearer.